Rauschenberg's New York, in Black and White

Photo by Lisa Freeman

The Museum of the City of New York marks Robert Rauschenberg's centennial with an exhibition that zeros in on the artist's relationship with photography and the metropolis that shaped his revolutionary vision. "Robert Rauschenberg's New York: Pictures from the Real World," running through April 19, presents 80 works exploring how the Texas-born iconoclast transformed New York’s urban detritus and his everyday observations into art that rewired American culture.

Curated by Sean Corcoran, the exhibition divides Rauschenberg's photographic practice into three sections: Early Photographs, In + Out City Limits, and Photography in Painting. The show reveals an artist who wasn't just appropriating found imagery but actively documenting the world with a bold creative vision. For Rauschenberg, the camera functioned as both sketchbook and documentation tool, capturing raw material that would later resurface in his combines, silkscreens, and assemblages.

Photo by Lisa Freeman

Born Milton Ernest Rauschenberg on October 22, 1925, in Port Arthur, Texas, he arrived in New York in 1950 after studying at Black Mountain College in North Carolina, where he learned from Josef Albers—though Albers reportedly called him "erratic," "sloppy," and "undisciplined." That contradictory relationship—rebellious student honoring strict mentor—characterized much of Rauschenberg's approach to artmaking.

By 1953, Rauschenberg had settled permanently in New York, establishing a studio near Coenties Slip in lower Manhattan alongside artists including Jasper Johns, Agnes Martin, and Ellsworth Kelly. The area was cheap, smelled of river air, and fostered the kind of creative ferment that allowed Rauschenberg to produce his most radical work. It was here he created "Bed" (1955), painting over an actual quilt when he lacked canvas, and "Monogram" (1955-59), featuring a stuffed angora goat with a tire around its middle—works that obliterated boundaries between painting and sculpture, high art and street trash.

Photo by Lisa Freeman

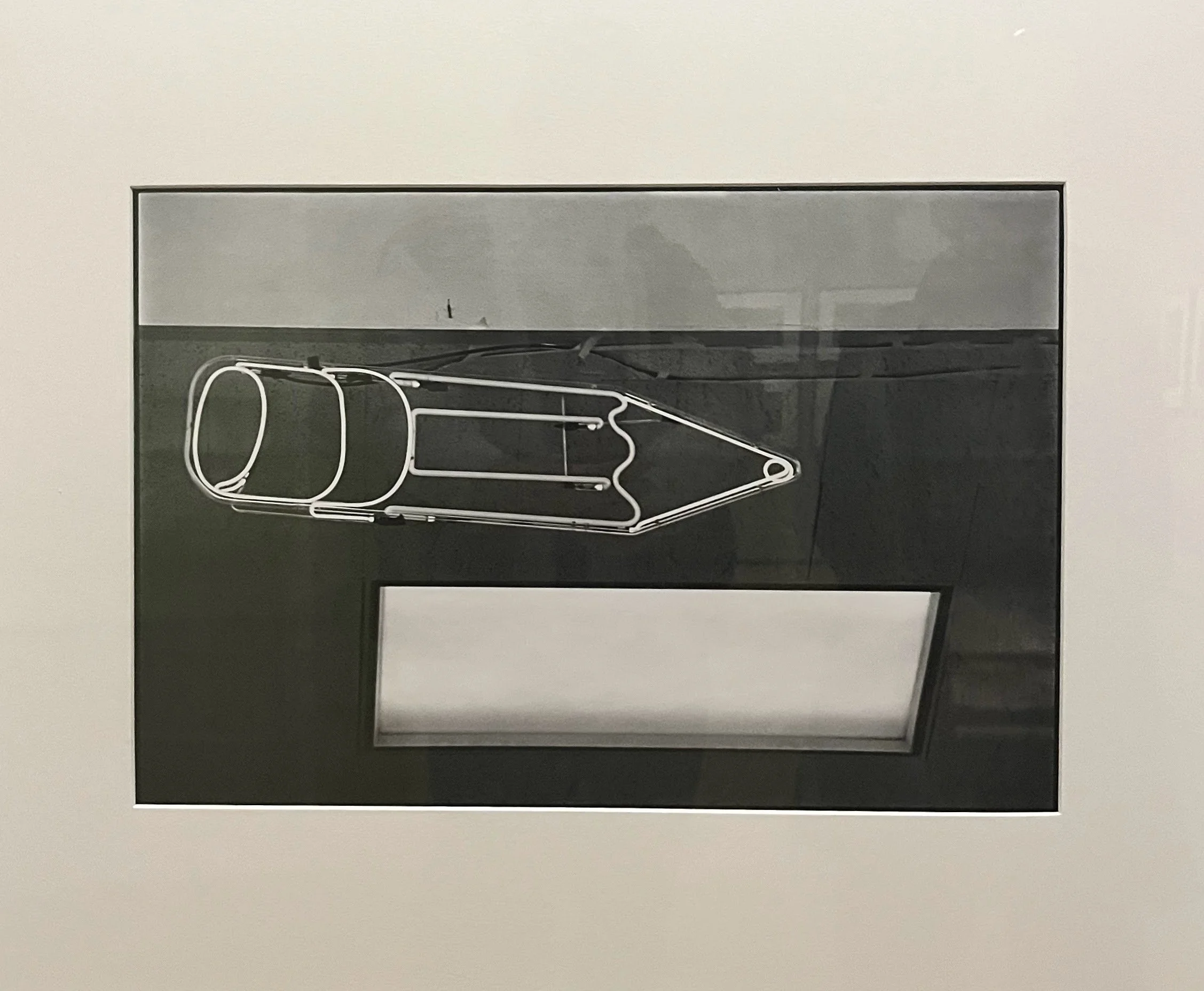

The MCNY exhibition includes intimate gelatin silver prints from Rauschenberg's later photographic surveys. One 1980 image shows a neon tube that forms the outline of a pencil glowing above a framed white rectangle—the kind of urban mark-making that fascinated Rauschenberg throughout his career. The photograph captures his eye for compositional tension: the loose, hand-drawn quality of the neon tubing contrasts with the rigid geometry of the frame below it, both elements grounded in the texture of a weathered, two-tone background.

Another photograph from 1983 demonstrates Rauschenberg's gift for finding surreal juxtapositions in everyday New York. The image splits into two horizontal registers: above, the sculpted face of the Statue of Liberty gazes upward with blank eyes; below, a young man in profile descends an escalator carrying a tray of cheeseburgers. The composition creates an accidental dialogue between monumental symbol and mundane moment, high culture and low—exactly the kind of collision Rauschenberg spent his career engineering.

The exhibition's core section features photographs from "In + Out City Limits," Rauschenberg's ambitious three-year road trip (1979-81) documenting America—an idea he'd been sitting on since his Black Mountain College days. The New York images from this project show an artist transfixed by street-level semiotics: faded advertisements, discarded signage, the visual debris that most people walk past without a second glance. Rauschenberg wasn't hunting for pretty compositions. He was tracking the city's transient moments with a photographer's discipline, trying to pin down experiences that typically evaporate before you can name them.

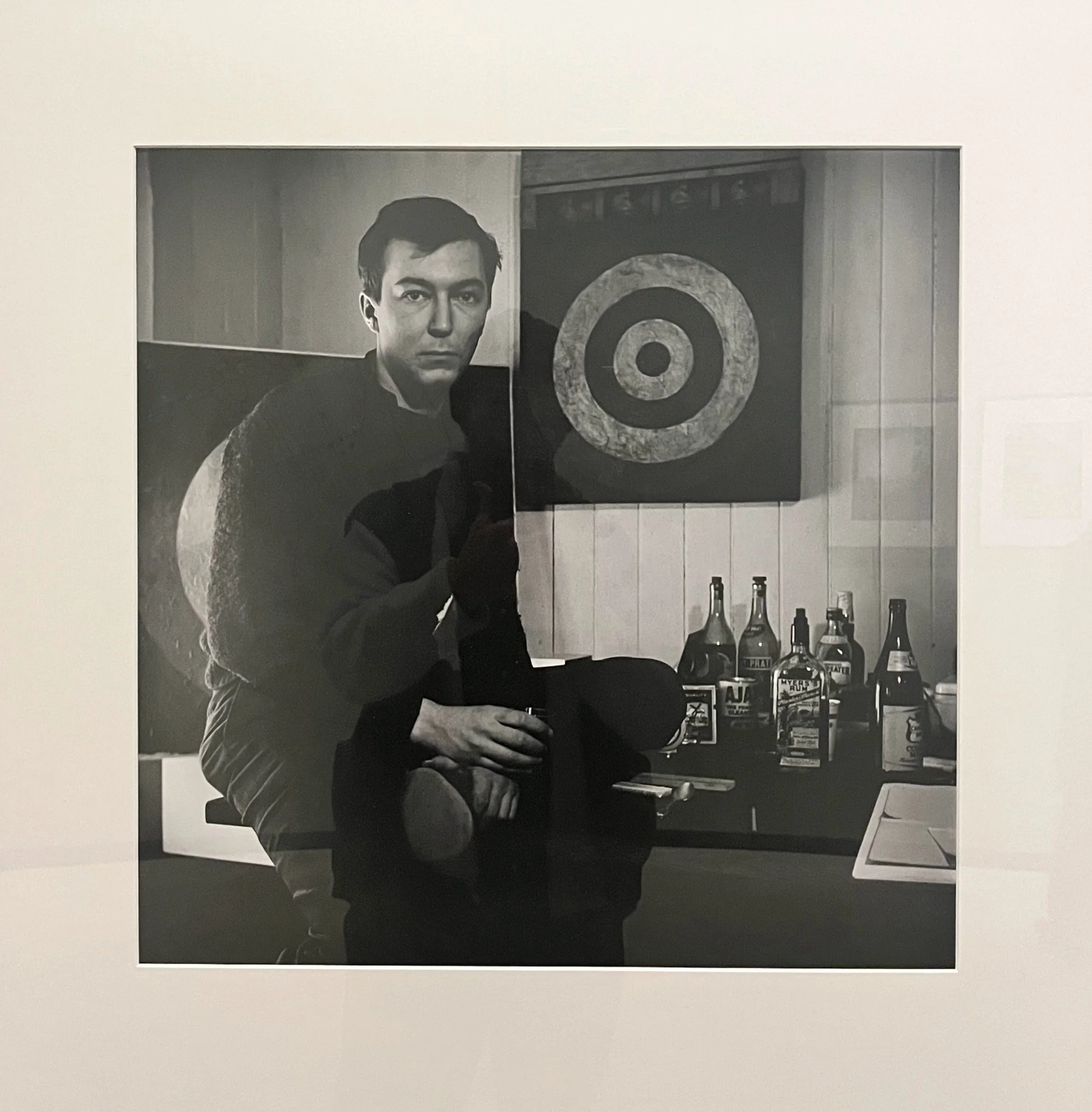

Portrait of Jasper Johns, “Jasper—Studio N.Y.C." (1958). Photo by Lisa Freeman

Rauschenberg's New York years coincided with his most productive period. Between 1953 and 1961, he was romantically involved with Jasper Johns, living and working in adjacent studios. The exhibition includes two portraits of Johns from this era. In "Jasper—Studio N.Y.C." (1958), Johns sits on a table littered with liquor bottles, his target paintings visible behind him. The photograph captures the downtown art world's bohemian intensity—a world Rauschenberg helped define.

The exhibition also presents works created between 1963 and 1994 combining Rauschenberg's New York photographs with images from around the world. A 1994 piece, "Wet Flirt (Urban Bourbon)," explodes with color—orange, yellow, blue, red, green—each hue occupying distinct quadrants yet bleeding into adjacent sections. Silkscreened images of industrial equipment and urban scenes fragment across the surface. It's classic late Rauschenberg: restless, layered, refusing resolution.

Wet Flirt (Urban Bourbon), 1994. Photo by Lisa Freeman

Rauschenberg once said he wanted to work "in the gap between art and life." The MCNY exhibition proves he found that gap on New York's streets, where thrown-away objects and chance encounters provided the material and the fuel for an artistic practice that would reshape that not-so-long-ago art world.

The show arrives during a banner year for Rauschenberg centennial celebrations, with exhibitions at the Guggenheim, Grey Art Museum, Walker Art Center, and venues worldwide. But this focused look at his photographic eye and urban obsessions reminds us that Rauschenberg was at times just a man with a camera, walking New York, seeing possibilities in everything.