Helen Frankenthaler at MoMA: A Grand Sweep Through a Legendary Practice

Helen Frankenthaler, Chairman of the Board, 1971, acrylic and felt-tip pen on canvas> Photo by Lisa Freeman

The Museum of Modern Art has installed five monumental works by abstract expressionist painter Helen Frankenthaler in its soaring second-floor atrium where the walls measure 110 feet floor to ceiling. Installations can easily be lost amid the room’s consuming whiteness, but this does not happen here, perhaps because the size of the atrium matches Frankenthaler's boundless ambition. It seems that her work, which for decades held its own amid the supersized egos of her largely male contemporaries, is unlikely to be swallowed up by mere institutional architecture.

Helen Frankenthaler: A Grand Sweep has been on display at MoMA since November, but if, like us, you’ve been otherwise occupied, the exhibition will be up until Feb. 8. It marks Frankenthaler's first solo moment at MoMA since a 1989 retrospective that, like the current show, drew on the museum’s extensive collection of Frankenthaler’s work.

Thirty-five years seems a long gap between shows for a painter who fundamentally altered what American abstraction could be. This certainly wasn't due to institutional neglect; MoMA has over the years acquired an extraordinary collection of some 70 Frankenthalers. More likely, MoMA sought to heighten impact via a strategic waiting period for an artist who remained active until the early 2000s. Also to its credit, MoMA signaled its respect for Frankenthaler by declining to so much as mention her marriage to abstract expressionist founder and lead spokesperson Robert Motherwell in any of its exhibition documentation. Other art institutions would do well to follow MoMA’s lead.

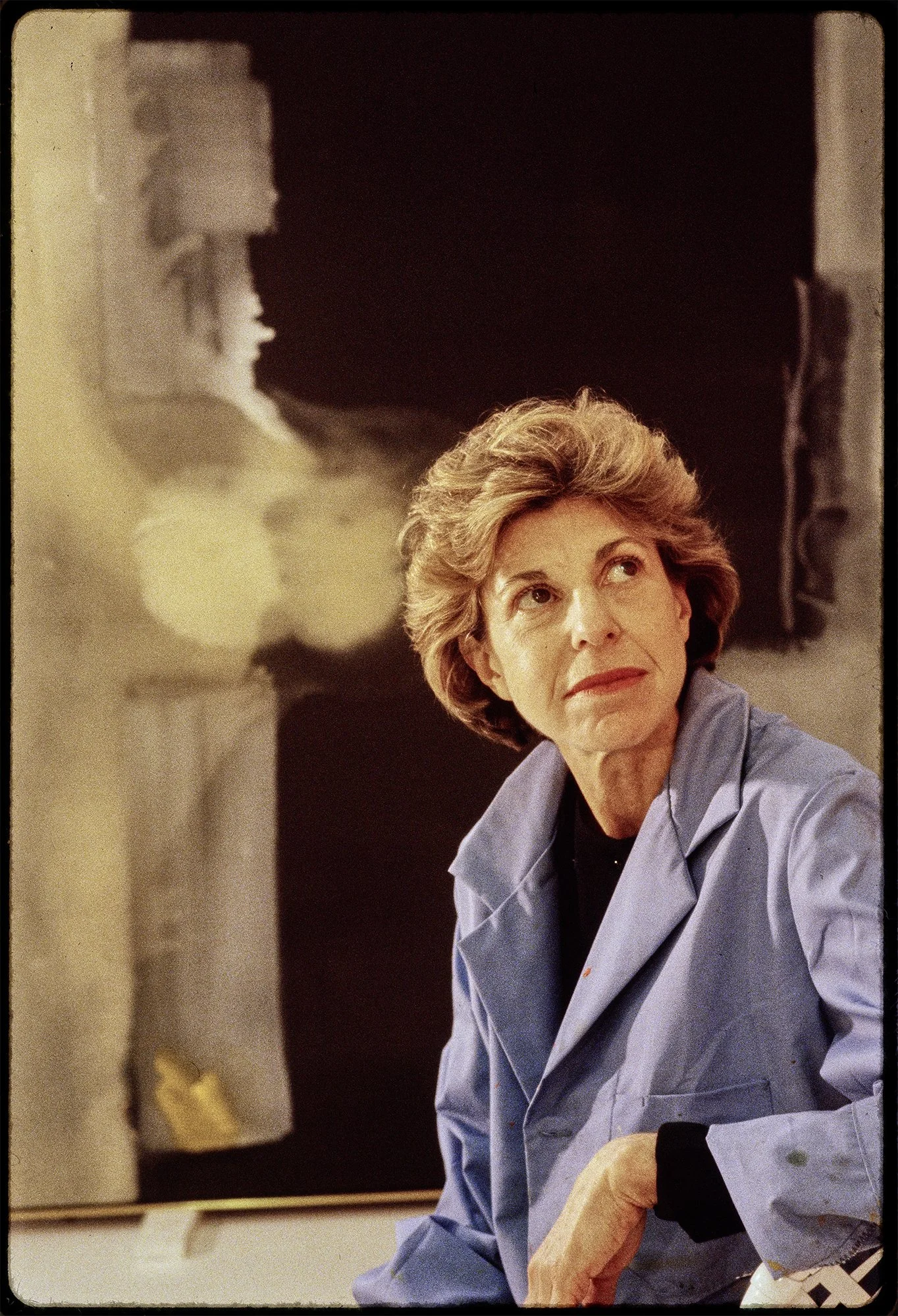

Helen Frankenthaler with Toward Dark in the background. Photo courtesy MoMA

The exhibition takes its title from Frankenthaler's own words about her 1971 work Chairman of the Board, which she said “was about a grand sweep. I had the basic idea in my head—I knew how the lines would dance in. I felt sure of myself.”

That confidence radiates from the canvas. Chairman of the Board sprawls across the wall in burnt orange, a landscape of thinned acrylic and felt-tip pen. The painting's central forms suggest a hammock suspended in space, or perhaps some geological formation viewed from above—rust-colored expanses punctuated by cream-colored channels and a curious purple-green nodule at the convergence point. By 1971, Frankenthaler had moved decisively into acrylics, which allowed for the crisp edges and chromatic clarity visible here. The addition of felt-tip pen introduces an almost cheeky element—high art meeting office supply, gesture meeting graphic mark.

The painting demonstrates what Frankenthaler meant when she described her forms in geographic terms, calling them "districts" or "territories." In this painting, she investigates how color and shape could map space without resorting to traditional perspective. The MoMA wall text notes her attention to "the relationship between painting and landscape," which undersells how radical her approach actually was.

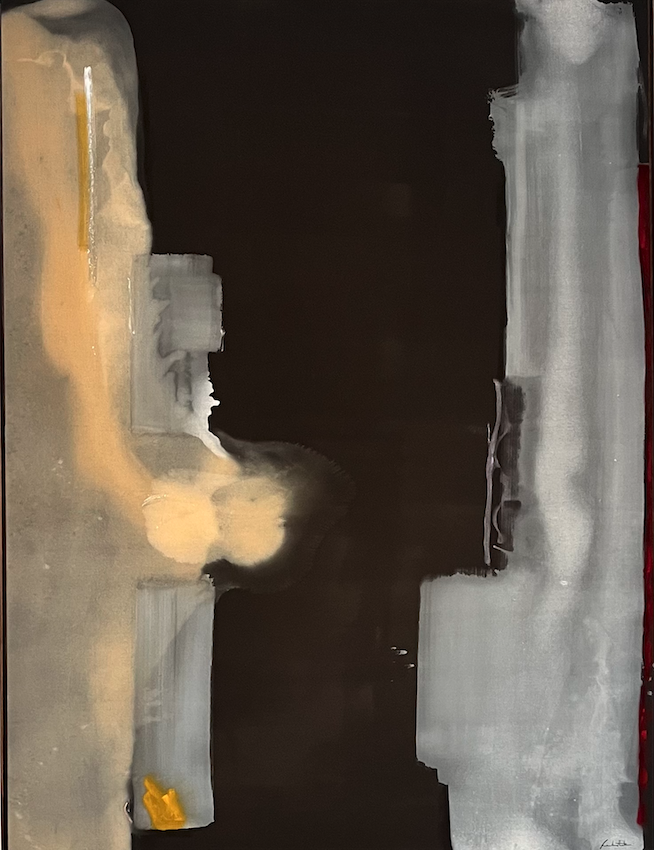

Toward Dark, 1988, acrylic on canvas, is making its MoMA debut. Photo my Lisa Freeman

Anchoring the installation is Toward Dark, a recent acquisition from the Helen Frankenthaler Foundation that is making its MoMA debut. Here's where Frankenthaler's late-career investigations into moodier palettes and subtle compositional shifts become evident. Pale gray-white columns bracket the edges while warm yellows and creams emerge from deep brown-black voids. A hint of deep red bleeds from the right edge, keeping the composition from sliding into monochrome.

As its name makes clear, the painting is about approaching darkness. The vertical elements suggest standing forms or architectural fragments, but Frankenthaler keeps everything hovering between representation and pure abstraction. She's not illustrating darkness; she's constructing it through calibrated tonal relationships and material investigation.

The exhibition also includes Jacob's Ladder (1957), a work Frankenthaler described as developing "into shapes symbolic of an exuberant figure and ladder." She named it after José de Ribera's Jacob's Dream (1639) from the Museo Nacional del Prado—a fact that complicates easy narratives about abstract painting's supposed rejection of art history. Frankenthaler was in constant dialogue with Old Masters, letting museum visits and encounters with European painting shape her visual language.

A man considers Jacob's Ladder, a 1957 oil on canvas. Photo by Lisa Freeman

By the 1950s, Frankenthaler had developed her signature soak-stain technique, pouring thinned oil paint onto raw canvas and allowing the medium to penetrate. The paint didn't sit on top of the surface; it became the surface. Works from this period, including Jacob's Ladder, possess an aqueous quality distinct from the thick brushstrokes that characterized her abstract expressionist contemporaries' canvases. In 1957, she explained: "If I am forced to associate, I think of my pictures as explosive landscapes, worlds, and distances held on a flat surface."

This technique would prove foundational for color field painting, influencing artists who sought to make their vibrant canvases as flat as possible by uniting medium and support. But Frankenthaler never stopped evolving. By the early 1960s, she'd shifted to acrylic paint, enabling more defined edges and precipitating what the museum describes as "a new emphasis on shape."

The biographical details MoMA provides sketch a portrait of privilege turned to purpose. The youngest child of a prominent Jewish household on New York's Upper East Side, Frankenthaler grew up with the resources and persistence to claim space. She studied with Rufino Tamayo during high school and Paul Feeley at Bennington College before returning to Manhattan in 1949. She began socializing with Lee Krasner, Willem de Kooning, Elaine de Kooning, and Jackson Pollock, whose method of painting on the floor rather than an easel would prove influential.

A view of the installation. Photo courtesy MoMA

In 1951, at age 22, Frankenthaler was the youngest artist in the 9th Street Exhibition, the cooperative coming-out party for Abstract Expressionism. "I think the luckiest thing at that moment," she later recalled, "was to be in one's early 20s with a group that you could really talk, live, and argue pictures about."

Frankenthaler’s vision unfolds across MoMA’s Marron Family Atrium with the kind of spatial generosity Frankenthaler's canvases demand. The museum has wisely let the work breathe, allowing visitors to experience what curator Samantha Friedman describes as "the ambition that defined Frankenthaler's work" without crowding the visual field.

Walking through these paintings, you're confronted with an artist who understood what she wanted to accomplish and systematically acquired the technical chops to execute it over decades of fearless material investigation. Frankenthaler's paintings don't need context beyond what's visible on the wall. They're too busy demonstrating what happens when confidence, innovation, and pure visual intelligence converge on canvas.

Helen Frankenthaler: A Grand Sweep is on view at The Museum of Modern Art, 11 West 53 Street, New York, through February 8.