Calder Gardens: Making Metal Breathe

Untitled (1952), 3 Segments (1973), and Jerusalem II (1976) in Calder Gardens main viewing space. Photo by Lisa Freeman

"Theories may be all very well for the artist himself, but they shouldn't be broadcast to other people," Alexander Calder once said. Calder Gardens, which opened last fall in Philadelphia, takes this principle as its organizing philosophy. No wall labels. No didactic texts. No fixed exhibition schedule. You enter through a meadow of native grasses and echinacea, descend through cave-like passages with rough shotcrete walls, and emerge into curved galleries where mobiles spin in air currents without anyone telling you what to see.

The contrast seems deliberate—gardens and geological passageways housing geometric steel sculptures. Calder's work has always operated in the territory between the engineered and the natural, between flat metal and three-dimensional space, between industrial materials and biomorphic forms. His sculptures are made from cold metal, bolts, and wire, yet they achieve something remarkably alive through elegant curves, friendly primary colors, and the way flat components assemble into shapes that evoke mountains, clouds, leaves, bodies in motion. The museum's design—with its pseudo-earthen walls and circular spaces—doesn't contrast with Calder's aesthetic. It mirrors it.

Jerusalem Stabile II (1976). Photo by Lisa Freeman

Jerusalem Stabile II (1976) dominates the largest gallery, a massive construction standing 12 feet tall and stretching 24 feet inches wide. All curved sheet metal and bolts painted in Calder's signature red, the piece presents as a giant mechanical creature. But look at how those arched elements work—they're flat industrial forms bent and positioned to suggest something alive, something that grew rather than was built. The curved sections create negative spaces that shift depending on where you stand. Walk around it and the sculpture becomes different animals, different architectural fragments, different abstract possibilities. Artist Jean Arp coined "stabile" in 1932 to differentiate these stationary works from Calder's mobiles, but "stationary" undersells what's happening. The curves imply movement even as nothing moves.

Hanging in the same space is 3 Segments (1973), three large black half-circles—utterly flat, utterly geometric—balanced against smaller circular elements on wire armature. Each piece is precisely weighted so the construction floats in equilibrium, responding to air currents. As the mobile turns, those half-circles slice through space, and suddenly they're not geometric anymore. They're leaves falling. They're waves. They're whatever your eye decides they are in that moment. Calder reduced his palette here to black and white, pure form and pure balance, but the result feels anything but reductive.

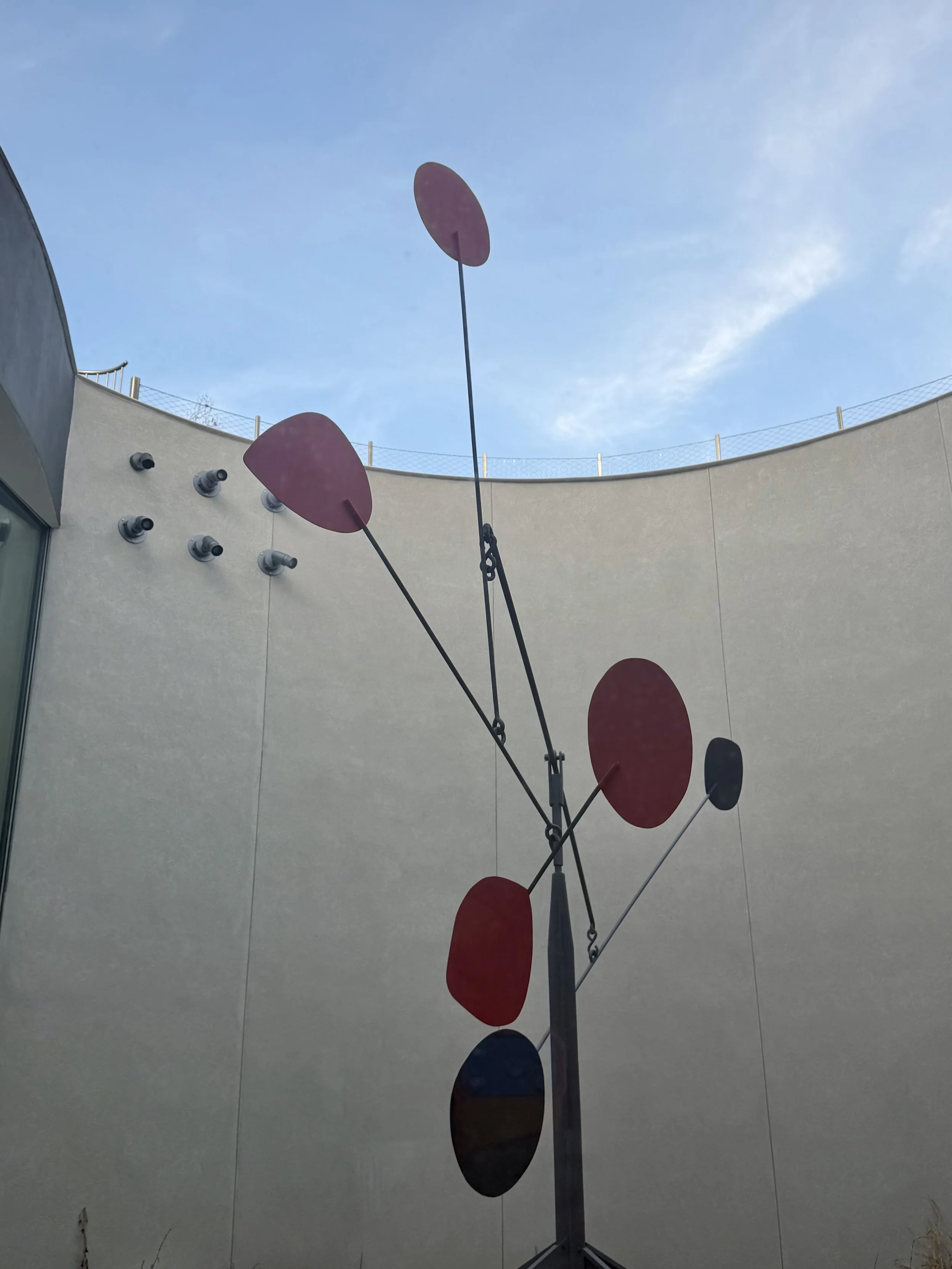

Untitled (1954). Photo by Lisa Freeman

Outside in a cylindrical sunken garden—walls that will eventually be covered in plants—sits an Untitled standing mobile from 1954. Pyramidal base, wire arms extending upward, holding red teardrops, a white circle, a black disc. It's the hybrid form Calder perfected: a stationary foundation supporting kinetic elements. The primary-colored shapes bob independently as wind hits them, moving at different speeds, creating new relationships between forms that last seconds before dissolving into different arrangements. The piece stands 13 feet tall among native plants, another integration that feels natural.

This is what Calder figured out after visiting Piet Mondrian's Paris studio in 1930. He described the space as containing rectangles of colored cardboard tacked to white walls, light coming from multiple directions, everything geometric and pure. "I suggested to Mondrian that perhaps it would be fun to make these rectangles oscillate," Calder recalled. "And he, with a very serious countenance, said: 'No, it is not necessary, my painting is already very fast.'"

Mondrian's refusal became Calder's breakthrough. Within a year, he'd created abstract sculptures with movable parts. Marcel Duchamp suggested "mobiles"—a French pun meaning both "motion" and "motive." Calder initially motorized these works but found them monotonous. His solution: hanging sculptures powered by air currents, constantly creating new relationships between forms. The innovation made geometric abstraction respond to natural forces.

Calder in his Roxbury studio, 1941. Photograph by Herbert Matter © Calder Foundation, New York.

Jean-Paul Sartre understood this in 1946 when he wrote that "Calder's objects are like the sea, and they cast its same spell—always beginning again, always new. A passing glance is not enough to understand them. One must live their lives, become fascinated by them."

Herzog & de Meuron's building operates ably amid its own contrasts. You descend through that dark stairwell with craggy walls—"the wormhole," director of programs Juana Berrío calls it—and the architecture feels geological, carved rather than built. Then you emerge into a light-filled space where stabiles present themselves as mobiles float above. The contrast isn't actually a contrast. It's the same transformation Calder's work performs: taking one thing and making it appear as its opposite.

The exterior metal facade does its own dance of contrast—its soft-focus surface picks up the gardens during the day and glows amber with the city's reflected lights at night. It duplicates and reflects what’s there, rather than asserting itself as architecture unto itself. The gardens extend this philosophy, dealing naturally with ambient movement and change just like Calder's sculptures.

Photo by Iwan Baan courtesy Calder Gardens.

The Philadelphia location carries weight beyond geography. Alexander Milne Calder (1846-1923), the sculptor's grandfather, created the 37-foot bronze William Penn statue that crowns City Hall plus more than 250 additional sculptures for that building. His son Alexander Stirling Calder (1870-1945) made the Swann Memorial Fountain on Logan Square. That’s three generations of Calders holding court within less than a mile. Calder Gardens occupies 1.8 acres on the last available Benjamin Franklin Parkway plot, positioned between the Barnes Foundation and the Rodin Museum.

The Calder Gardens make loud the artist’s refusal to theorize. His sculptures don't require interpretation because the physical experience does that for us, naturally. They move. They balance. They transform flat metal into dimensional space, geometric forms into living suggestions, cold materials into warm experiences.

Calder Gardens, 2100 Benjamin Franklin Parkway, Philadelphia.