When Down Was Up: Revisiting '80s NYC at Lévy Gorvy Dayan

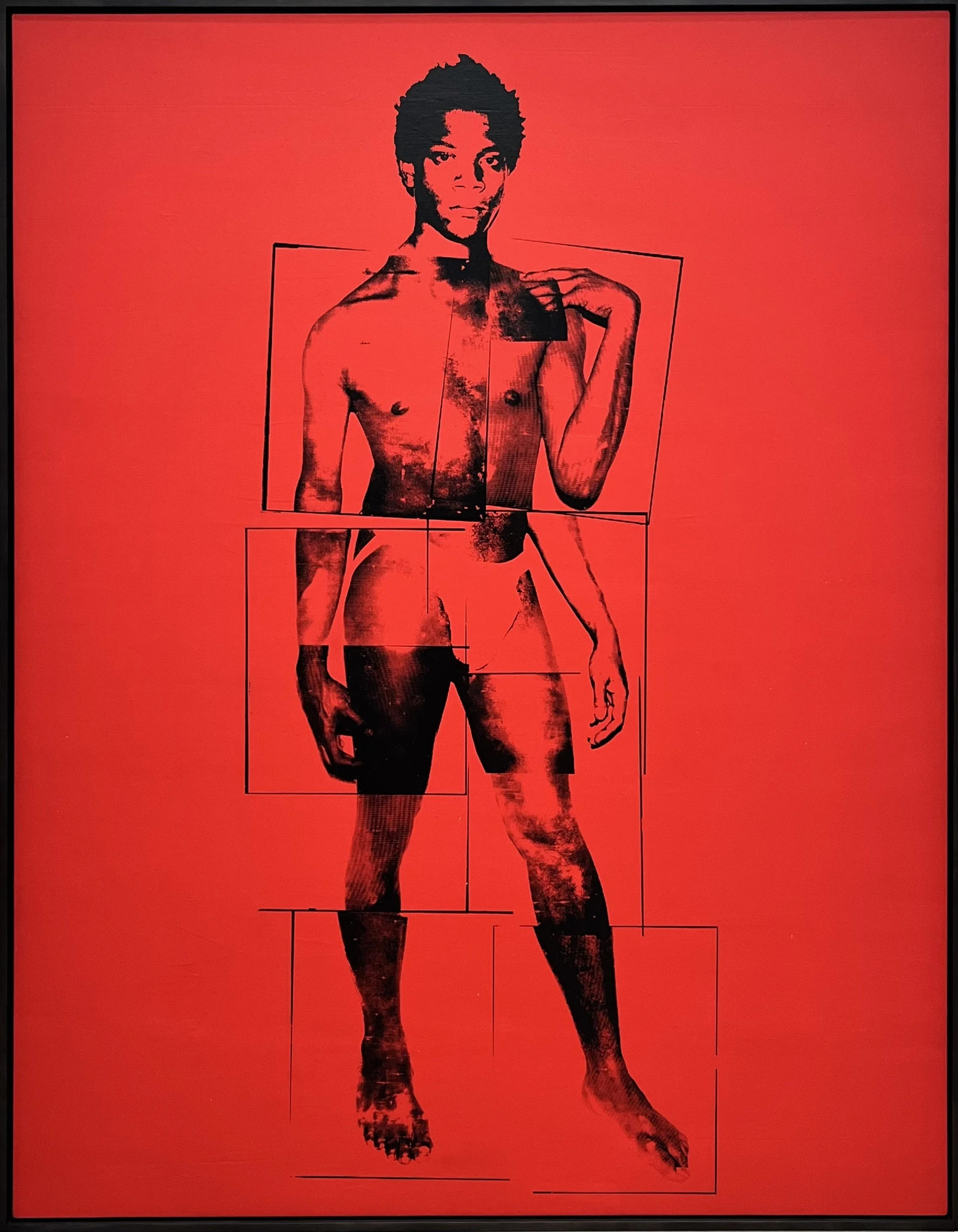

Andy Warhol Reel Basquiat, 1984

The first thing you see on entering Lévy Gorvy Dayan's Beaux-Arts style townhouse on East 64th Street is a monumental silkscreen portrait of Jean Michel Basquiat wearing nothing but a jock strap. Set against an electric red background, the subject is rendered in black, a collage of snapshots pieced together slightly off kilter, but enough to portray an artist whose genius is not perfectly formed. In this 1984 portrait of Basquiat, his friend and collaborator, Andy Warhol, captured everything about '80s art: the need to shout above cultural noise, the wholesale packaging of sexuality, the anxiety beneath all that manic energy and the commodification of, well, everything. Warhol stretched his appropriation techniques to capture a moment when artists were succeeding by their own rules amid ceaseless competition in the media-saturated landscape exploding all around them.

Now, more than four decades after Warhol created Reel Basquiat, Lévy Gorvy Dayan's Downtown/Uptown: New York in the Eighties resurrects the period’s chaos, assembling some of the decade's heaviest hitters anew. The show was organized with legendary gallerist Mary Boone—one of the most significant players in the artistic maelstrom that was downtown Manhattan of the day and one of those who helped mainstream the likes of Basquiat, Keith Haring, Barbara Kruger and others at a time when downtown was making an historic uptown push.

The show’s central theme—that the '80s represented a collision between high and low, uptown refinement and downtown grit—is nothing new. But Downtown/Uptown is more than that. It’s also about adjacent themes of youthful weightlessness, untamed ambition, post-modern dread, consumerism, profit and the full spectacle of capitalism. What Warhol started with that first soup can, this generation advanced with the energy and abandon of cocaine and Quaaludes.

Jean-Michel Basquiat Untitled, 1982

The show maps the decade's contradictions through carefully chosen works. Jean-Michel Basquiat's explosive canvases explain why he became art's first Black superstar. The exhibition summons as bookends Untitled (1981), a text-and-image work that demonstrates how graffiti's raw vocabulary infiltrated gallery walls, and Gravestone (1987), a supercharged triptych that memorializes at once the late Warhol and the decade itself. In between, there was Untitled 1982—a skull-faced figure emerging from an electric blue background, painted in Basquiat’s signature furious and urgent style. The piece embodies the decade's manic energy while carrying undertones of mortality that would prove tragically prescient.

Keith Haring, Untitled (Pink Happy Face), 1981

Keith Haring's Untitled (1984)—that grinning face rendered in his signature cartoon style—captures the decade's naive optimism before decadence and disease brought the whole thing tumbling down. There's something almost pharmaceutical about Haring's imagery, as if happiness itself could be commodified and packaged to medicate the masses. The work functions as both celebration and warning, embodying the period's drug-induced euphoria while hinting at its inevitable comedown.

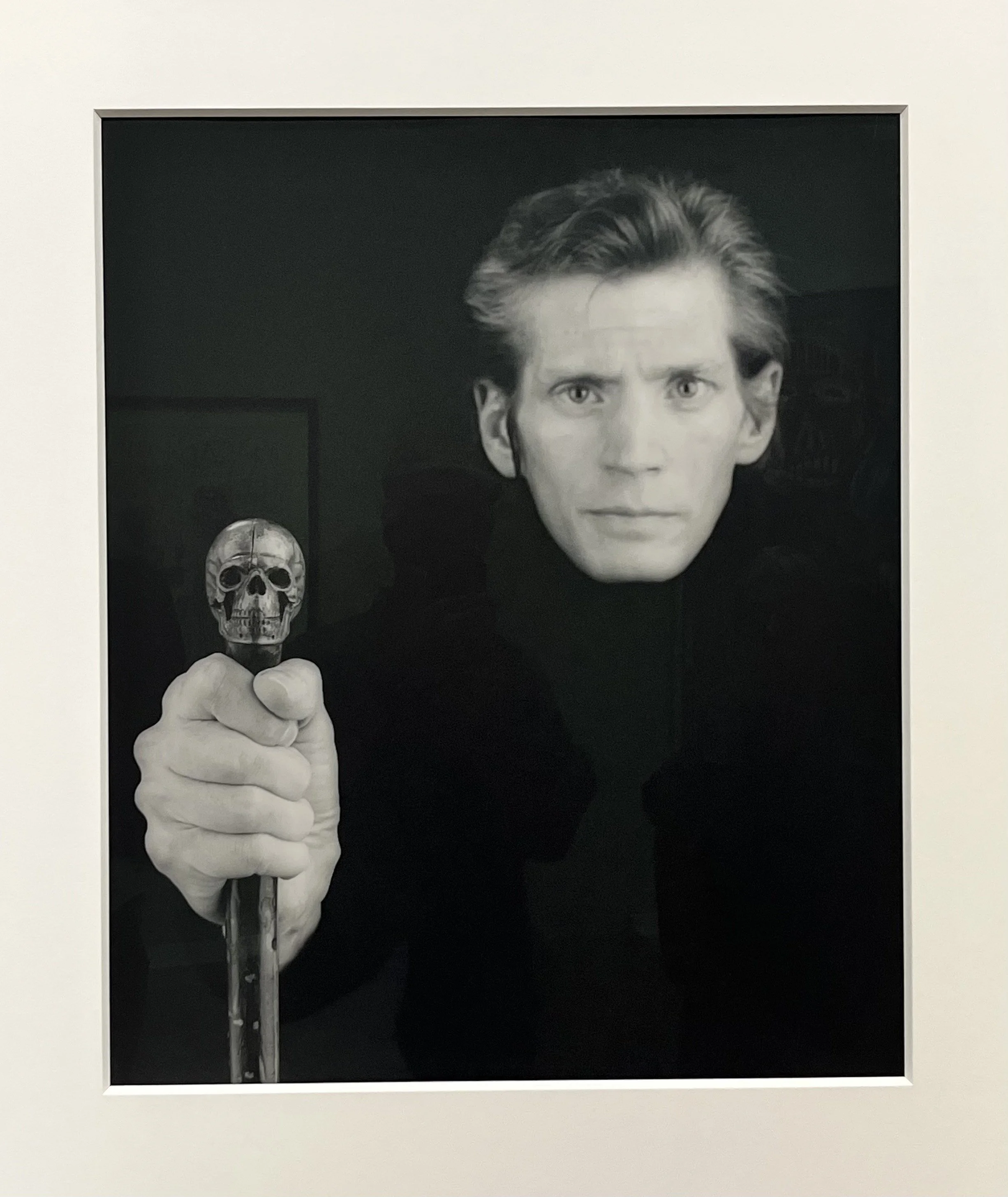

Robert Mapplethorpe Self-Portrait, 1988

Consider also Robert Mapplethorpe’s haunting 1988 self portrait, a gelatin silver print that captures the photographer’s disembodied visage clutching a skull-topped cane just months before his death. The photograph operates on multiple registers simultaneously—as documentation of an artist at work, as memento mori, and as prescient commentary on the decade's obsession with death. The skull-cane is at once a prop and a symbol of the AIDS crisis that would devastate the art world within years.

Barbara Kruger Untitled (You invest in the divinity of the masterpiece), 1982

Barbara Kruger's untitled 1982 work appropriates the finger touch moment from Michelangelo's "Creation of Adam," overlaying it with the message “You invest in the divinity of the masterpiece” in her signature red bars and bold typography. Here, she suggests that in greed-is-good New York, witnessing the masterpiece is no longer enough, now you must also invest in it.

The show's sculpture selection is equally revelatory. Jeff Koons's New Shelton Wet/Drys series (1981-86) transforms humble vacuum cleaners into totemic objects through the simple act of gallery presentation. These aren't readymades in Duchamp's sense—they're late-capitalist relics, consumer objects elevated to art status through sheer force of institutional will. Where Warhol offered reproductions of consumer products, Koons offered the products themselves.

The diversity of styles and techniques issues a portrait of a downtown art scene in the grip of its own unlikely success, blurring the line between the gallery world and pop media. As Peter Nagy, artist and cofounder of Nature Morte Gallery, said in a 1983 interview, the scene was "on the verge of becoming something it's never been before. More in the vein of popular culture, movies, television, fashion."

The exhibition also demonstrates how these artists persisted even as their critical edges were being buffed by unprecedented commercial success. They understood that authenticity in the '80s meant embracing inauthenticity, that the only honest response to media saturation was more media. They weaponized mixed messages, celebrated sarcasm, courted engagement through considered expression, and made the gallery system itself part of their artistic practice.

Jean-Michel Basquiat, Gravestone, 1987

Mary Boone's collaboration on this project adds crucial context. She wasn't just selling these works in the day—she was manufacturing the mythology that made them valuable. Her SoHo gallery became a laboratory for art world transformation, where painting could be both commodity and critique, where artists could be both rebels and entrepreneurs.

Downtown/Uptown succeeds because it refuses to sanitize this legacy. The '80s art world was messy, contradictory, and occasionally brutal. It produced genuine masterpieces alongside cynical market manipulation. It launched careers and destroyed lives. It left many behind. It democratized art while making it more expensive than ever. The exhibition presents this complexity without judgment, allowing viewers to draw their own conclusions about creativity and drive on one hand, power and money on the other, which is what Downtown/Uptown means after all, isn’t it?

Walking through these rooms today, surrounded by works that now command eight-figure prices, it's impossible not to feel nostalgic for a moment when art could still expand its own ecosystem. There’s a saying in Gotham that the only thing that doesn’t change in New York is how much people talk about how New York has changed. So nostalgia is cheap around here. Maybe a better lesson to take from this latest exploration of the '80s art big bang is that every generation must find its own way to make revolution on its own terms. These artists didn't just make great work—they changed the rules of what great work could be and told future generations to do the same.

Downtown/Uptown: New York in the Eighties runs through December 13, 2025, at Lévy Gorvy Dayan, 19 East 64th Street.