Man Ray's Revolutionary Vision Gets Its Due at the Met

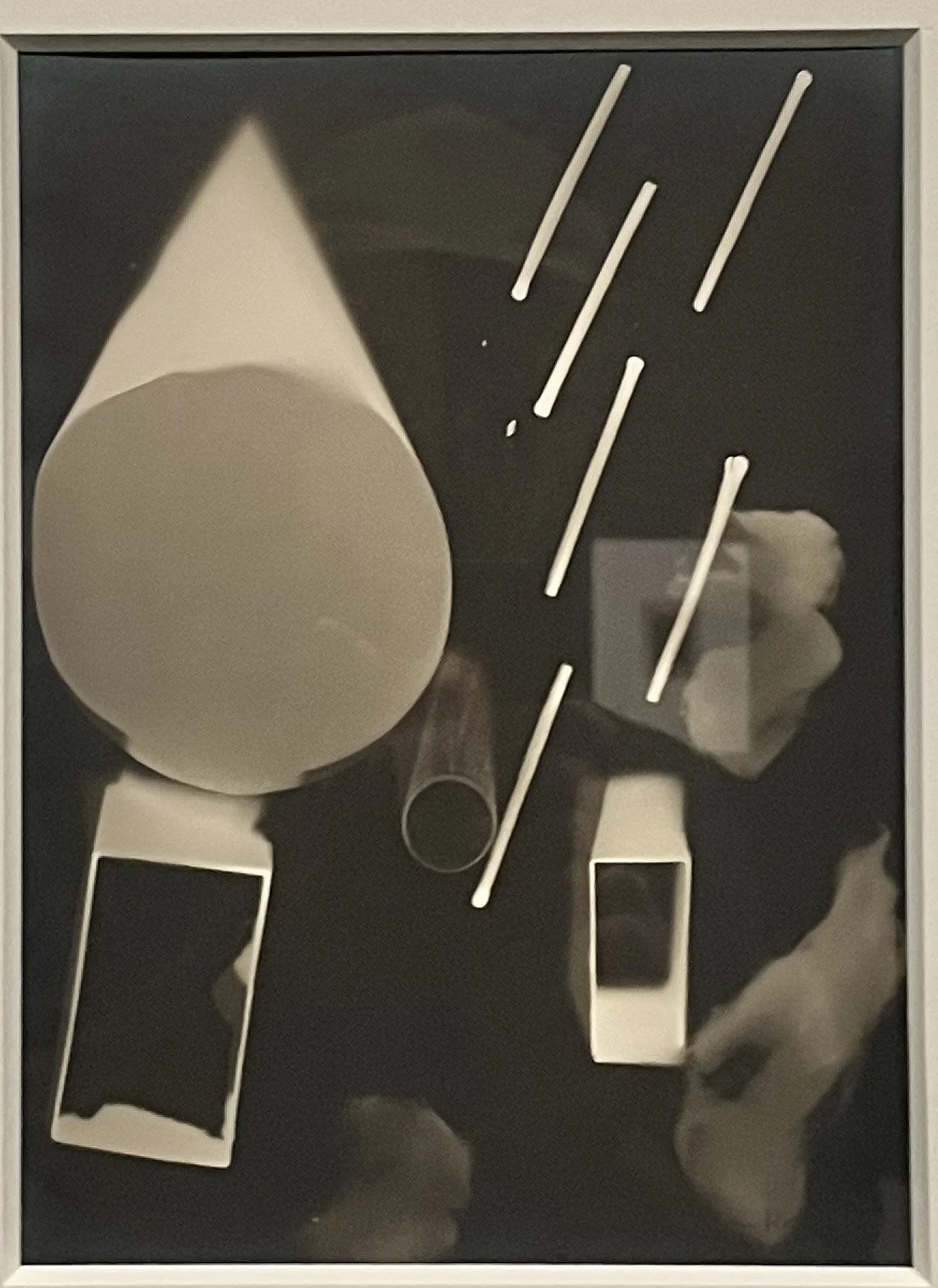

Twelve rayographs greet visitors at the Met's new show Man Ray: When Objects Dream

It is said to have started with a darkroom accident in 1921. Man Ray had been working late in his Paris studio when some glass equipment fell onto an unexposed sheet of photographic paper. As the image developed before his eyes, something extraordinary happened—objects became "distorted and refracted," transformed into mysterious silhouettes that seemed to hover between dream and reality. These "rayographs," as he'd name them, would become one of his most important contributions to a movement that was just finding its footing between the wreckage of Dada and the emergence of Surrealism.

A century later, as the art world marks the 100th anniversary of André Breton's First Surrealist Manifesto, the Metropolitan Museum of Art is giving Man Ray his proper due. "Man Ray: When Objects Dream," running through February 1, 2026, is the first major exhibition to position the rayograph at the center of the American artist's radical practice. It's about time.

Rayograph, 1922

Walking through Gallery 199, you're immediately struck by the central drama of these photograms—twelve haunting compositions from his 1922 portfolio "Champs délicieux" (Delicious Fields). The pairing captures something essential about Man Ray's relationship with his own invention: these weren't just technical experiments but poetic statements that bridged the gap between the anti-art rebellion of Dada and Surrealism's exploration of the unconscious.

The exhibition makes clear that Man Ray’s contribution to the evolution of contemporary art goes far beyond his camerawork. Curators have woven together 160 works—paintings, sculptures, photographs, and films—that reveal how this "accident" actually represented the culmination of everything Man Ray had been working toward since arriving in New York's avant-garde scene around 1915. Here was an artist who had already been pushing against medium boundaries, and the rayograph became his ultimate expression of creative freedom.

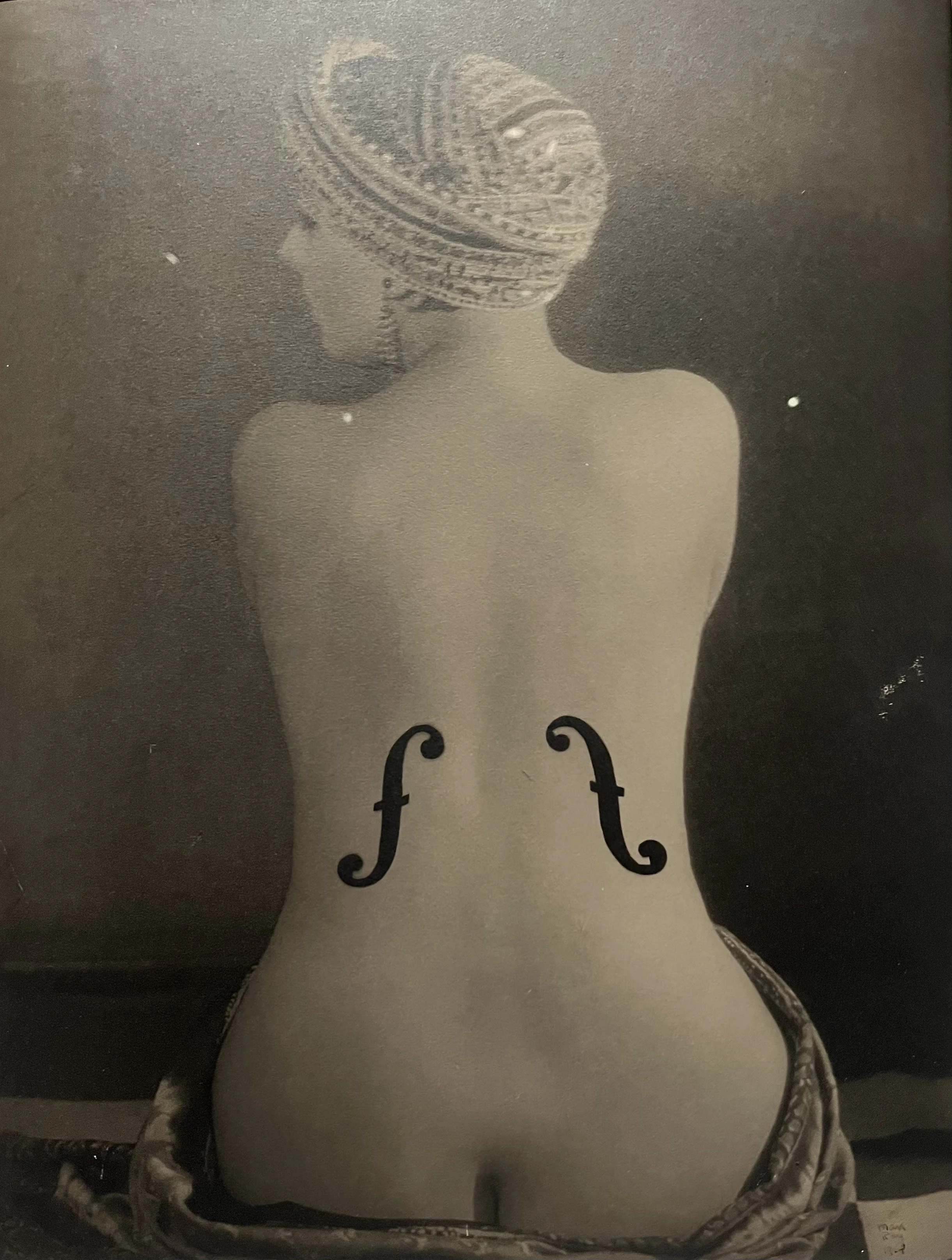

Le violon d'Ingres, 1924

The famous works are all here: the impossible violin drawn onto Kiki de Montparnasse's back in "Le violon d'Ingres," the metronome fitted with Lee Miller's eye in "Object to be Destroyed," the iron studded with tacks called "Cadeau." But the real revelation comes in seeing how these pieces connect to his lesser-known paintings like "Paysage suédois" (Swedish Landscape).

Man Ray occupies a unique position in Surrealism's history. He was the only American to play a major role in both the Dada and Surrealist movements, and his technical innovations—rayographs, solarization with Lee Miller, his experimental films—embodied the movement's faith in chance and the unconscious. As museums worldwide celebrate Surrealism's centennial with major exhibitions, the Met's focus on Man Ray is particularly relevant.

Marchesa Luisa Casati, 1922

Three newly restored films—"Retour à la raison," "Emak Bakia," and "L'étoile de mer"—screen within the galleries, reminding us again that Man Ray’s ground-breaking photography was hardly his only critical contribution to the Dada and surrealism movements

What emerges is a portrait of an artist who understood that innovation meant more than technical breakthrough—it required reimagining the relationship between artist, medium, and viewer. Examining the transformative nature of rayographs, Dada poet Tristan Tzara described them as capturing moments "when objects dream." A century on, Man Ray’s revolutionary work still suggested that liminal dreamspace where the familiar becomes fantastic, where everyday items transform into poetry.