Jasper Johns’ Radical Reorientation, the Crosshatch Paintings at Gagosian

Between the Clock and the Bed (1983), oil on canvas. Photo by Lisa Freeman

Fifty years after their debut at Leo Castelli Gallery, Jasper Johns' crosshatch paintings returned to New York in a survey at Gagosian's Madison Avenue flagship, forcing a long-overdue reassessment of what may be the most misunderstood period of the 95-year-old artist's career.

The crosshatch works were produced during a decade-long immersion in abstraction that severed Johns from the iconographic certainties that made him famous. After building an entire reputation on what he called "things the mind already knows"—flags, targets, numbers, the readymade lexicon of American visual culture—he deliberately pivoted toward something the mind emphatically does not know. These paintings offer no handrails, no shared cultural references, just interlocking diagonal slashes that forego narrative and symbolism in favor of their own relentless logic.

Yet to call them purely abstract misses the point. Johns took a technique historically deployed in printmaking and drawing to create the illusion of depth and volume and made it the content itself—a move that essentially flipped the relationship between method and meaning. The crosshatch becomes simultaneously subject and object, a kind of visual tautology that operates according to what Johns termed "simple mathematical variations."

Corpse and Mirror (1974), oil, encaustic and collage on canvas. Photo by Lisa Freeman

The Corpse and Mirror series (1974-84) epitomizes this tension. The 1974 diptych in the exhibition—two joined panels measuring 50 by 68 inches—employs the crosshatch as both structural armature and conceptual framework. The left panel presents dense, interwoven strokes in blacks and whites, newspaper fragments poking through the encaustic surface. The right panel mirrors this vocabulary but inverts its chromatic and directional logic. The title itself—lifted from the surrealist parlor game exquisite corpse—implies collaborative authorship and chance operations, yet Johns exercises total control over these aleatory systems.

Even more audacious is Weeping Women (1975), Johns' sprawling triptych that measures 50 by 102 inches across its three joined panels. Here the crosshatch becomes a vehicle for historical dialogue, specifically with Picasso's Weeping Women series of the 1930s. While Picasso's series channeled the anguish of Guernica and the Spanish Civil War through the distorted face of Dora Maar, Johns drains the motif of its original pathos, reconstituting it through the mechanical repetition of his hatch marks. The left panel vibrates with reds and grays, the center with ochres and blacks, the right with blues—each section suggesting figuration while remaining abstract.

Weeping Woman (1975), oil on canvas. Photo by Lisa Freeman

The density of these works also demands attention. Johns deployed encaustic, collage, acrylic, oil paint, watercolor, ink, and even sand, building up bold surfaces that aspire to three dimensionality. In his encaustic crosshatch paintings, Johns incorporated collaged newspaper scraps that created thick, impasto-like surfaces. These fragments of newsprint catch the viewer's eye, introducing temporal markers and linguistic content into ostensibly non-referential compositions.

The exhibition's title work, Between the Clock and the Bed (1981-83), brings together all six paintings in this series for the first time—a rare opportunity to see Johns' dialogue with Edvard Munch's self-portrait (1940-43) of the same name. Munch's painting shows the Norwegian artist standing between a grandfather clock and a bed with a crosshatched quilt, providing Johns with both formal precedent and existential framework.

What makes these crosshatch works genuinely radical isn't their formal invention—plenty of artists have worked with geometric abstraction—but their retreat from the mythologies that sustained Johns' early career. The flags and targets operated in a zone of shared cultural legibility; everyone knew what an American flag meant, which made Johns' deadpan presentation of it simultaneously obvious and deeply strange. The crosshatch paintings refuse this social contract.

This might explain why the crosshatch decade has been somewhat marginalized in popular consciousness compared to the 1950s iconography. The early work photographs well, reproduces clearly, and slots neatly into narratives about Neo-Dada and Proto-Pop. The crosshatch paintings resist such easy assimilation. They're difficult, austere, demanding—qualities that paradoxically make them more relevant now than when they first appeared. At a moment when painting constantly justifies its continued existence, Johns' crosshatch works demonstrate what the medium can do that nothing else can: sustain complex, nonverbal investigation of perception, meaning, and material

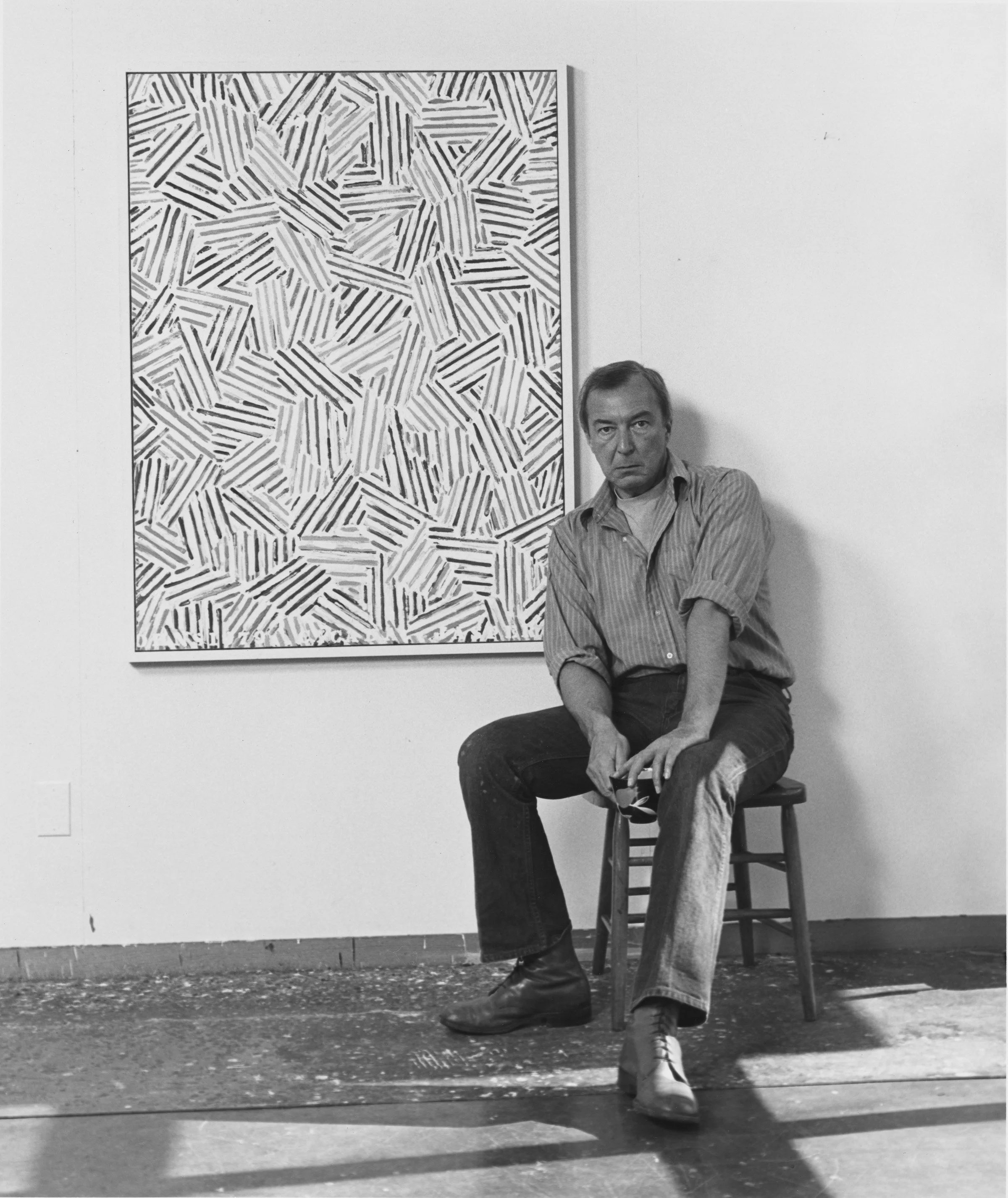

Jasper Johns in his studio, c. 1976–80 © 1991 Hans Namuth Estate Photo: Hans Namuth Courtesy Center for Creative Photography, University of Arizona

Johns turned to abstraction just as painting itself entered crisis—a moment when painting appeared exhausted, retrograde, incapable of sustaining serious investigation. His response wasn't to defend painting's traditional prerogatives but to hollow them out from within, creating work that looks like painting but operates according to different protocols. The crosshatch paintings acknowledge their own arbitrariness—"order with dumbness," as Johns put it—while executing that arbitrariness with such rigor and conviction that it transcends its own stated meaninglessness.

The exhibition runs through March 14—enough time to sit with paintings that reward patience and punish haste. These aren't works that give themselves away in Instagram-friendly moments. They require the kind of sustained, physical engagement that runs counter to contemporary viewing habits. Which might be exactly the point. In an era of infinite digital reproduction and instant visual consumption, Johns' crosshatch paintings insist on their irreducible materiality, their refusal to be anything other than what they are: paint on canvas, arranged according to systems that are simultaneously arbitrary and absolute.

Between the Clock and the Bed: Jasper Johns is at Gagosian, 980 Madison Avenue, through March 14.