In Miami, Street Art’s Unstoppable Ascension

Jessica Goldman Srebnick, curator of Wynwood Walls, introduces the incoming class of artists. Photo by Lisa Freeman

WYNWOOD — Every December, two parallel art universes collide in South Florida, separated by just three miles of Biscayne Bay but divided by decades of mutual suspicion, aesthetic differences, and class warfare. On one side of the bay, Art Basel Miami Beach—the Western Hemisphere’s most important contemporary art fair—unfolds along with a dozen other fine art fairs. On the other, Wynwood’s street art epicenter attracts those who have embraced the ascendance of street art as a globally important movement.

This year, as the fine art fairs struggle with a dodgy market and blue chip galleries bail, the mood among the linen suit and champagne set seems a bit subdued. Here in Wynwood, though, there is a sense of optimism and anticipation among the beer-drinking crowds in sneakers and tee shirts that gather beneath towering murals committed in spray paint by tomorrow’s fine art masters. Once an afterthought, the street art component of Miami Art Week finally seems ready to assert itself.

Joe Iurato at Wynwood Walls. Photo by Lisa Freeman

Joe Iurato, the New Jersey street artist whose star has risen dramatically of late, said he appreciates the value of the events on both sides of the bay, though he focused all his attention on Wynwood this year. “Normally, I would have stuff in SCOPE and stuff, but this year I was solely focused on this,” he says, noting he has a new mural in Wynwood Walls and artwork in its Goldman Global Arts (GGA) gallery. “It’s nice to see street art or graffiti being placed on the same plane as what others consider fine art. Because this is fine art. It’s the most honest expression.”

Iurato gathered with established and ascending street artists the other night for a party celebrating street art’s rise at Wynwood Walls, the open air gallery that has played no small role in street art’s evolution to legitimacy in the art world.

Shepard Fairey, one of those who has surfed the crest of street art’s ascendancy to international art stardom, said street art provides an egalitarian entry point into an evolving mainstream art landscape. In the street art world, he said, “there’s a generous spirit to it rather than making sure that there’s an intimidation factor that makes people feel like they aren’t qualified to appreciate the art without an interpreter. That’s what I like about this—it’s sort of free for everyone to feel included.”

“And then, of course, there’s fine art iterations of all that kind of work that do use the more typical gallery model because people need to survive. But I think the difference is a different outlook on preciousness,” he said.

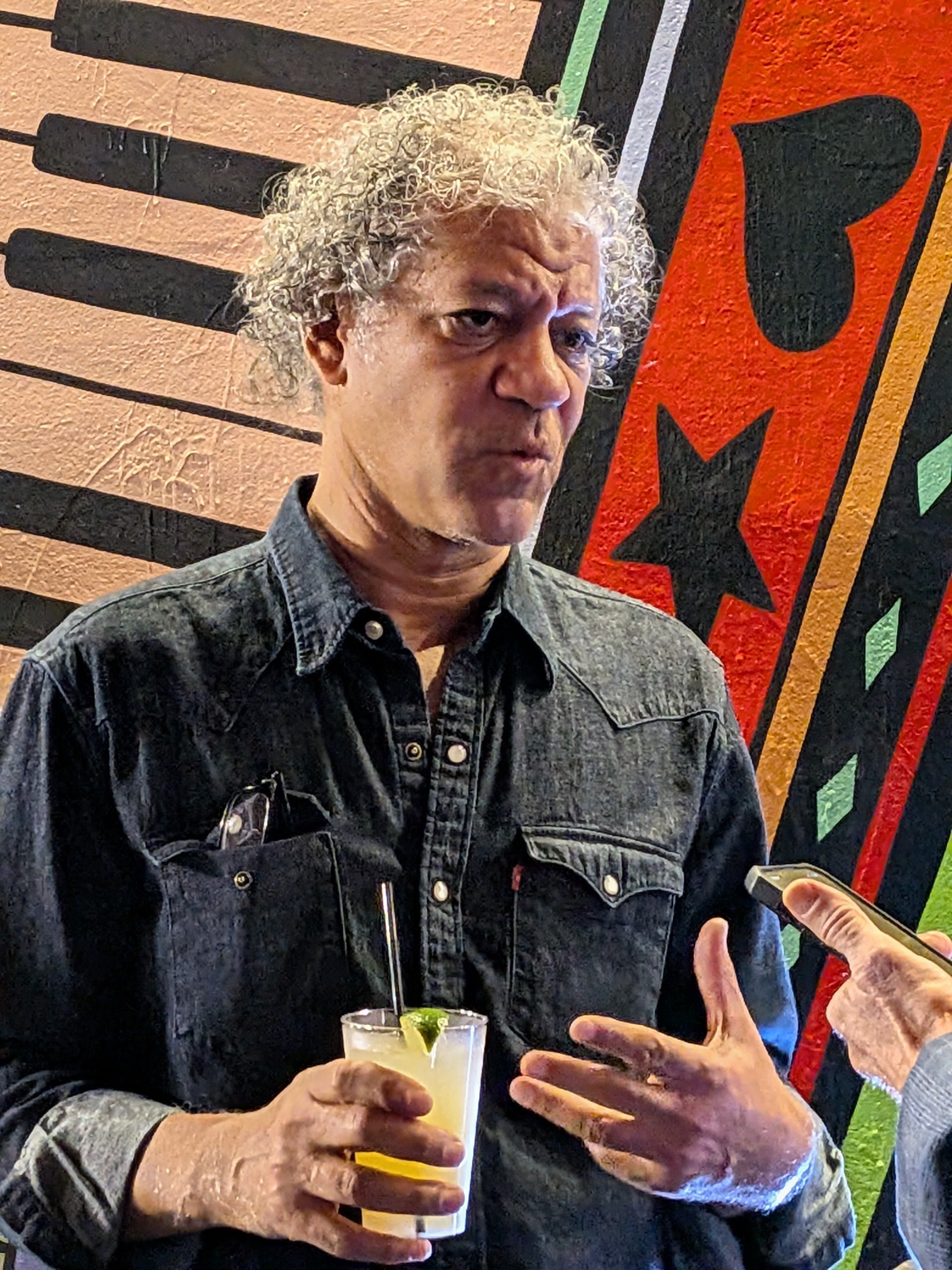

Shepard Fairey talks with quests at the Wynwood Walls party. Photo by Lisa Freeman

In Miami, the cross-bay battle lines have been blurring for years now. Street art, once dismissed by the establishment as vandalism dressed up with artistic pretensions, has become one of the most commercially successful and culturally influential art movements since the Pop Art revolution in the 1960s. The graffiti writers and street artists who built their reputations painting illegally on subway cars and abandoned buildings are now commanding the kind of prices and institutional respect that would have seemed impossible a generation ago.

Daze, a first-generation graffiti writer who has witnessed street art’s tortured path to legitimacy from the beginning, said that, like many street artists, his work has evolved and matured along with the movement. “It’s just a kind of natural evolution as an artist. People that have followed me and been on my journey can see that,” he said.

Daze. Photo by Lisa Freeman

There’s nothing new about street artists making the leap into the gallery world. Jean-Michel Basquiat was one of the first, evolving from a member of the downtown graffiti writing duo of SAMO with Al Diaz into a historically significant neo-expressionist master before his death in 1988. Keith Haring followed a similar trajectory and is now ensconced in art fairs, galleries and museums worldwide. Kenny Scharf is another great example of an artist who parlayed street cred into spots into acceptance in the fine art world. Work by street art superstars like Banksy and KAWS routinely sell for a million dollars.

For Miami Art Week 2025, Wynwood Walls offered up “ONLY HUMAN,” a theme exploring what remains uniquely human amid rapid technological growth. The exhibition debuts murals by Cryptik, Iurato, Miss Birdy, Persue, Quake, SETH, and RISK. For the first time in 12 years, El Mac and RETNA reunite for a joint mural and collaborative canvases.

“Technology may replicate patterns, but it cannot feel. It cannot know what it means to lose, to love, or to hope,” said Jessica Goldman Srebnick, curator of Wynwood Walls. “True creativity is born from the heart and grows through unshakable passion and the courage to do what others have not. This is uniquely human.”

The Museum of Graffiti, celebrating its sixth anniversary during Art Week, opened two major exhibitions on December 3rd. “Origins” traces graffiti culture from the 1970s to today, featuring original paintings by United Graffiti Artists members PHASE2, FLINT 707, SNAKE 1, and COCO144 that haven’t been seen since their 1973 debut—marking one of the first moments graffiti entered a gallery setting.

“Tracking down rare artifacts like this was always part of our mission so that the true history of graffiti can be shared in the most authentic way,” said Allison Freidin, co-founder of the Museum of Graffiti.

Miss Birdy, left, with Jessica Goldman Srebnick, curator of Wynwood Walls. Photo by Lisa Freeman

Alongside “Origins,” the museum presents “El Tiguere,” a solo exhibition by JonOne (John Andrew Perello), who began painting trains in Harlem before rising to global recognition as a contemporary painter based in Paris. The museum will feature a working studio where JonOne creates pieces in real time.

“I have been following Jon’s artistic journey since the 1980s in New York City and marvel at what he has accomplished with his signature tag. Once vilified, we now celebrate his artistic genius,” said Alan Ket, Museum of Graffiti co-founder.

Ket sees street art as “the biggest art movement of our time and perhaps the biggest art movement that the world has seen outside of digital art. This is an art movement that is in every major city around the world and has been going on for over 50 years.”

The tension between commercial success and street credibility remains real, but increasingly beside the point. Collectors who once dismissed graffiti as urban blight now compete for works by KAWS and Banksy. Blue-chip galleries that wouldn’t have touched street art 20 years ago actively court artists with street credentials. Art Basel and its satellite fairs increasingly feature work by artists who built their reputations one illegal mural at a time.

“This world, this art world of graffiti street art has infiltrated the mainstream art world and fairs all over the world,” Ket explained. “These are artists that have been working for decades in the streets and coincidentally in the studio, creating incredible works of contemporary art. I’m not surprised that it’s being accepted or being shown more in fairs. I’m surprised that it’s taken so long.”

The path street art provides into previously closed markets represents a fundamental disruption. “It’s really about determination. It’s really about networking and it’s also of course always about talent,” Ket said. “The elite fairs, the elite world, that’s just about money. If you’re not getting in there it really requires more relationship building than anything. The artists from the street art community get older and savvier and just know how to navigate the system better.”

The champagne and linen suits can coexist with beer and tee shirts. Street art has conquered not just walls and bridges but auction houses and art fairs. The graffiti writers and street artists aren’t waiting for permission anymore. They don’t need it. The gatekeepers, it seems, were optional all along.