Louise Bourgeois’s Psychological Abstraction at Hauser & Wirth

Louise Bourgeois, Gathering Wool, 1990 metal, wood and mixed media. Photo by Lisa Freeman

When Louise Bourgeois created Gathering Wool in 1990, she gave physical form to rumination itself—the mental drift between consciousness and dream, that space where thoughts fragment and reform without permission. The installation is the centerpiece of the exhibition Louise Bourgeois: Gathering Wool, which opened Nov. 6 at Hauser & Wirth's 22nd Street location. It consists of seven wooden spheres positioned before a tall four-panel screen, with small mushrooms emerging from the wood's fissures.

The gallery says the title of the work references an expression meaning daydreaming or letting the mind wander—"a break from conscious, purposive thinking." Gathering Wool, both the piece and the exhibition, marks a pivot point in understanding Bourgeois's relationship to abstraction, an often overlooked facet of her seven-decade career that has often been rarely studied and little understood.

The show focuses on later work from Bourgeois, the French-born multi-media artist who famously channeled childhood trauma and parental obsession into artwork that defies easy interpretation. In the years before her death in 2010, Bourgeois drew on her troubled relationship with her mother to create monumental abstract sculptures and installations, often starting with found objections and materials. Bourgeois’swork is notoriously difficult to categorize, so let’s just call it psychological abstraction rooted in autobiography

Hauser & Wirth President Marc Payot, left, and Philip Larratt-Smith who curated the show. Photo by Lisa Freeman

“It's the first major show of her work at the gallery here in New York,” said curator Philip Larratt-Smith as he led a walk-through of the exhibit during a press opening for the show. Larratt-Smith is a New York-based writer and the curator of The Easton Foundation, which administers Bourgeois’s legacy.

“I think you'll see that it's a show that relates to a side of Louise that is less well known. It's not spiders or cells. It focuses on other works, some of which have never been seen before and others that haven't been seen in a generation.

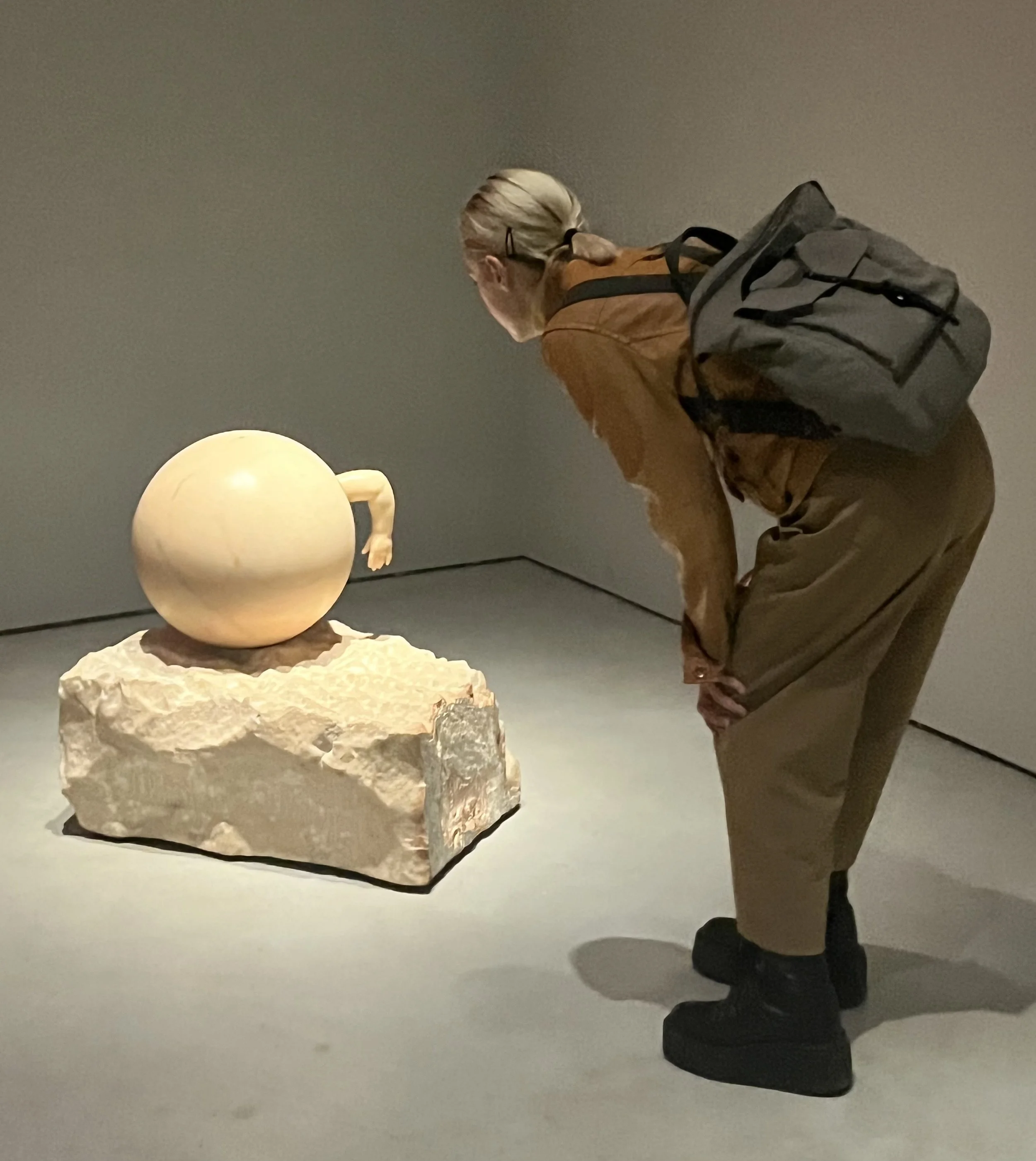

A woman examines Untitled (With Hand), 1989, pink marble, by Louise Bourgeois. Photo by Lisa Freeman

Sharing gallery space with Gathering Wool is Untitled (With Hand) (1989), a sculpture in pink marble that exemplifies what the press materials call Bourgeois's "iconography of things protruding out of other things." A child-like arm extends from a large sphere—vulnerable, reaching, trapped. The piece pulses with the psychological charge that defined Bourgeois's entire practice.

Gathering Wool opens with Twosome from 1991, a room-sized mechanized sculpture with a smaller tank that endlessly moves in and out of a larger tank—the mother-child relationship reduced to steel and motion. The same gallery screens footage from her 1978 performance A Fashion Show of Body Parts, featuring actress Suzan Cooper belting "She Abandoned Me."

The works illuminate some of the devices Bourgeois deployed as emotional shorthand. Repetition signified obsession and compulsion. Precarious balance indicated fragility. Interlocking forms were safeguards against abandonment—a fear that haunted her from childhood, when her father's affair with the family's English governess poisoned the household for a decade. As Bourgeois wrote, "I am the author of my own world with its internal logic and with its value that no one can deny."

Larratt-Smith explained that Bourgeois’s oeuvre evolved from one focusing on her tortured view of her father, to one steeped in the ties she felt to her mother. At the same time, she turned to abstraction drawn from found items rather than those she created herself. “I think it's because as she was getting older, she needed a heightened sense of reality to give her a way to achieve the kind of psychological discharge that she sought through making art.”

“So she's really exploring the mother-child relationship, describing the fundamental relationship, that sense of pattern of the whole future,” Larratt-Smith said. “This is an important shift that starts happening in the late 1980s where Louise is increasingly using real objects in addition to made objects, things that she would fabricate or produce herself,” he added.

A short time later, she began creating her celebrated Cells. The term "Cell" carried multiple meanings for the artist: the biological cell of a living organism, the isolation of a prison cell. As Bourgeois described them in a catalog issued at the time, "The Cells represent different types of pain: the physical, the emotional and psychological, and the mental and intellectual." Between 1989 and 2008, she created approximately 60 of these architectural enclosures, assembling found objects, personal artifacts, and her own sculptures within distinctive cages of wire, wood, and metal.

But let's talk about the spiders, those monumental arachnids for which Bourgeois is best known. There is, of course, Maman (1999), 30 feet high and 33 feet wide, cast in bronze, stainless steel, and marble, with a sac containing 32 marble eggs beneath its abdomen. The work was created for Bourgeois's inaugural commission at Tate Modern's Turbine Hall in 2000. Six bronze editions followed, now installed at major institutions worldwide.

Louise Bourgeois, Maman, 1999, Tate. © The Easton Foundation. Photo © Tate (Marcus Leith).

"The Spider is an ode to my mother," Bourgeois said at the time. "She was my best friend. Like a spider, my mother was a weaver. My family was in the business of tapestry restoration, and my mother was in charge of the workshop. Like spiders, my mother was very clever. Spiders are friendly presences that eat mosquitoes. We know that mosquitoes spread diseases and are therefore unwanted. So, spiders are helpful and protective, just like my mother."

The spiders embody contradiction: protector and predator, strength and fragility. Bourgeois's mother died when the artist was 21. Days later, she threw herself into the Bièvre River to be rescued by her father.

Born in Paris on Christmas Day 1911, Bourgeois worked in America from 1938 until her death in 2010. Recognition arrived late—she was 70 when MoMA gave her a retrospective in 1982. Her breakthrough interview with Artforum, timed to the retrospective's opening, marked the first time she publicly connected her work to her traumatic childhood.

"My emotions are my demons," she said. "It is not the emotions themselves—the intensity of the emotions is much too much for me to handle and that is why I transfer them, I transfer the energy into the sculpture."

Along with the late-career abstractions, the exhibition also includes earlier figurative works, demonstrating how "the same psychologically charged emotions which gave rise to Bourgeois's more figurative works also underpin the formal devices in her more abstract works," the gallery said. On the fifth floor, vertical progressions and stacked forms dominate—Bourgeois imposing regularity on emotional chaos.

The exhibition is the latest public display of Bourgeois's pained facility at transforming abandonment, jealousy, and rage into art. She used whatever form could, figuration or abstraction, found materials or made ones, to contain the pressure of her psychological excavations. As she said in an interview, "Art is the experience, the re-experience of a trauma."

The exhibition runs through January 24, 2025, at 542 West 22nd Street. Bring your demons.

Louise Bourgeois: Gathering Wool is on view through January 24, 2025, at Hauser & Wirth New York, 542 West 22nd Street.