At Hauser & Wirth: Franz Gertsch’s Monumental Patti Smiths

The crowd at a walkthrough of Franz Gertsch. Presence at Hauser & Wirth. Photo by Lisa Freeman

Franz Gertsch was walking past a record store in Bern when Patti Smith stopped him cold. Not the punk poet herself—her image, as captured in Robert Mapplethorpe's iconic 1975 photograph on the cover of her debut album Horses.

"He was not acquainted with Patti Smith," said curator Tobia Bezzola as he led a press walkthrough of Franz Gertsch. Presence at Hauser & Wirth's Soho location. "He walked past a record store in Bern, and he saw in the window her record Horses with the famous photograph, and he was immediately fascinated by this person. So he goes inside, he purchases the record, and then he learns that she is supposed to do a performance at a venue in Cologne," said Bezzola, director of the Museo d’arte della Svizzera italiana in Lugano, Switzerland.

What happened next would become art world legend. The Swiss painter, then in his late 40s, traveled to Cologne and positioned himself in the audience with his camera. "He's there in the audience, and he takes a series of images of Patti Smith," Bezzola continued. "Famously, he annoyed her because he was walking around with his camera and disturbing her poetry reading, so she was not very happy. There's even one portrait where she really hisses and snarls at him. Later they reconciled, as you can see,” he said.

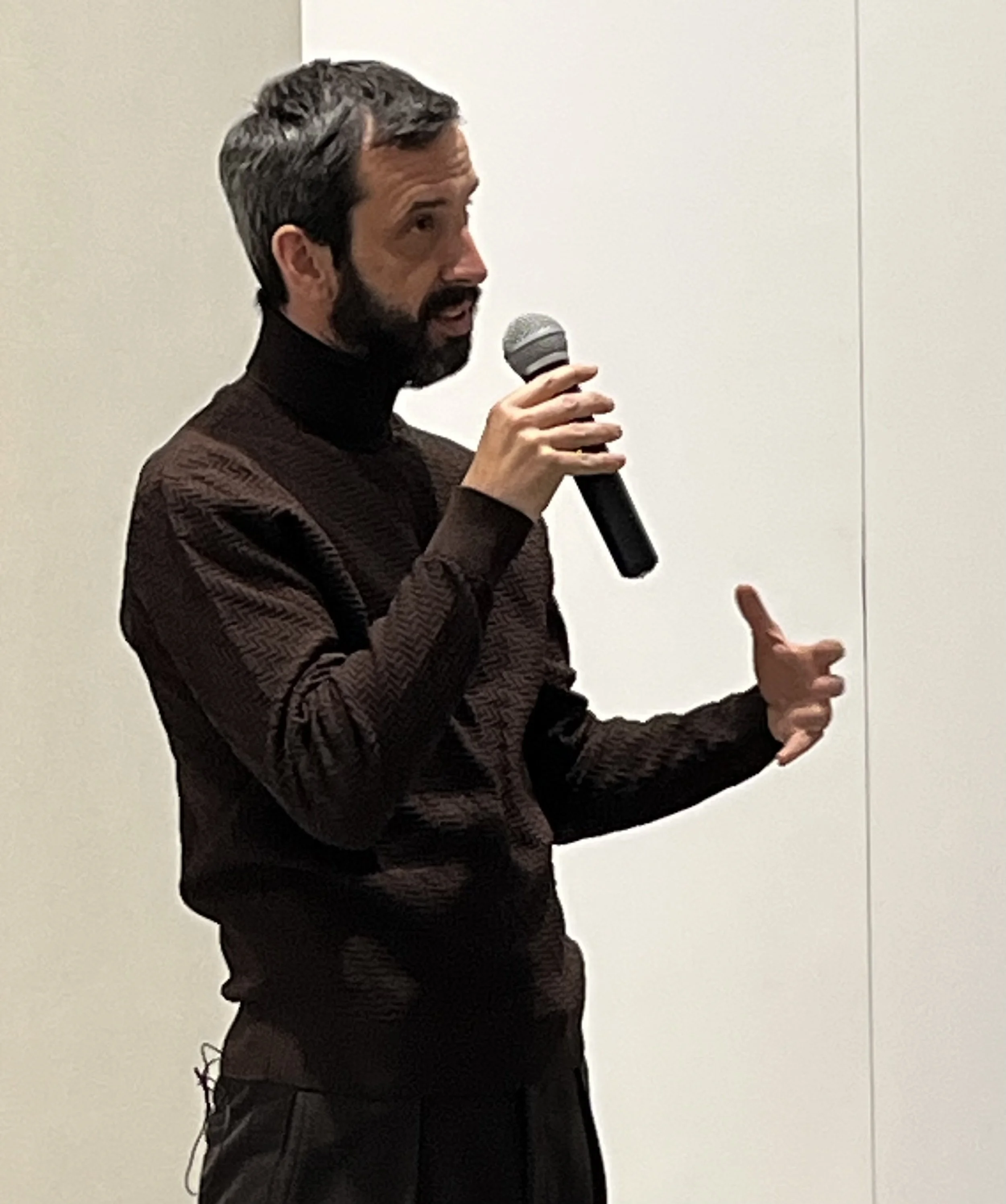

Curator Tobia Bezzola discusses the work of Franz Gertsch during a press walkthrough at Hause & Wirth. Photo by Lisa Freeman

Gertsch applied his signature technique to those photographs, turning them into a series of five monumental hyperrealistic acrylic paintings. Two of those paintings anchor the exhibition at Hauser & Wirth—the gallery's first comprehensive New York presentation of an artist who spent decades proving that painting could be more immediate, more visceral than the photographs inspiring it. The show brings together eight works spanning Gertsch's career, from the 1979 Patti Smith canvases through his pioneering woodcuts to late landscape paintings that dissolve documentary precision into near-hallucinatory vision.

Born in Mörigen, Switzerland in 1930, Gertsch left school at 17 to study under abstract-impressionist Max von Mühlenen, defying his father’s wish that he pursue a career as a piano teacher. Traveling in Europe in the late 1950s and early ’60s, he absorbed Pop Art’s vivid palette before developing his signature method in 1969: projecting his own photographs onto canvas, a modern take on the Renaissance camera obscura. Each hyperrealist painting took months or a year to complete.

The two wall-sized portraits of Smith (who by the way visits New York this month as part of her tour celebrating the 50th anniversary of Horses) steal the show. Patti Smith III captures her in profile, wild hair creating a dark halo against white space as she leans into the microphone. Every strand of hair seems individually rendered, the image glowing with stage light. In Patti Smith IV, she's caught full-face, eyes closed or nearly so, lost in the poetry. Beyond their astonishing verisimilitude, very close inspection reveals hints of the textures and touches of Gertsch's brush. These are paintings that achieve what photography cannot—they force you to recognize the density of time compressed into pigment.

Swiss artist Nicolas Party discusses his relatioship with the work of Franz Gertsch at Hauser and Wirth. Photo by Lisa Freeman

For Swiss artist Nicolas Party, who led a walkthrough before the public opening, Gertsch's work provided crucial education as he began studying art. Both artists share Swiss roots and faced similar pressures toward abstraction in their formative years. "You just ask yourself, 'What am I going to paint, and why am I going to paint it?'" Party said. "And I think, like Franz Gertsch, I turned very quickly to the most traditional and most obvious subjects, which were basically landscapes and portraits."

Yet Party admits a fundamental difference in temperament. "I'm not that patient as an artist and I want to go quickly very often," he said. "Gertsch is a very strong example of that practice of being like, 'Okay, the time that I have—we don't have all the time in the world—I'm just going to completely not be stressed out and just spend as long as it takes to make these incredible objects.' And it's very fascinating," Party said.

The exhibition traces Gertsch's dramatic pivot during the 1980s toward monochrome woodcut prints on handmade Japanese paper. "In 1980, it all comes to a stop," Bezzola said of Gertsch’s photorealistic technique. "He says, 'I can get no further with this way of doing art.' So for the next five years, there's almost no output, but there is a big, major development. He turns to the woodcut, which is a paradox, as you know. Woodcuts are not usually used for very realistic renderings. It's a very rough technique that ever since the Renaissance has been used to give bold outlines, black and white, harsh, big contrasts. You would not use woodcuts in order to give subtle modulations of light and dark," he said.

Franz Gertsch, Guadeloupe (Triptych) Bromelia, Maria, Soufrière, 2011 - 2013. Photo by Lisa Freeman

Yet Gertsch approached a local carpenter to create massive wood plates, had custom chisels and knives made, then spent years carving each light point from the wood surface. He traveled to Japan to work with papermakers creating sheets with exactly the right thickness and texture, and ground his own pigments to achieve precise effects.

"And I feel like with him—I mean, of course—he definitely chose a way of painting that was extremely unusual and in a way that completely isolated him from trends," Party said. "But I guess some people work better that way. I'm definitely on his side of it. I like to be isolated."

The immersive triptych Guadeloupe (2011-2013) emerged from photographic studies of Caribbean forest, with dense foliage and shifting light verging on abstraction. With its nude centerpiece, Maria, which honors Gertsch's wife and lifelong companion, the piece combines portrait and landscape, Gertsch’s favorite subjects.

Detail, Patti Smith IV, Franz Gertsch, 1979. Photo by Lisa Freeman

Bezzola knew Gertsch from childhood in Bern and collaborated with him on exhibitions at Kunsthaus Zürich (2011), Museum Folkwang (2015), and MASI Lugano (2019). Gertsch was grouped with American hyperrealists like Chuck Close at documenta in 1972, but never embraced that association. "He never felt that he was really understood when people thought that his final goal was to achieve the effect of a photograph," Bezzola explained. "Because as you can see in the show and as I've tried to explain, it's really much more about departing from the photograph, going through the photograph, and going beyond the photograph in order to create visual experiences which photography cannot provide."

Gertsch represented Switzerland at the Venice Biennale in 1999, and his woodcuts were first shown at MoMA in 1990. In 2002, with Swiss industrialist Willy Michel, he established the Museum Franz Gertsch in Burgdorf, with galleries proportioned specifically for his massive works. He died in 2022.

Franz Gertsch. Presence runs through January 31, at Hauser & Wirth, 134 Wooster Street, Soho.