At Gagosian: Photography’s Tragic Heroine Francesca Woodman

Francesca Woodman’s Blueprint for a Temple II is a monumental photo collage executed via 24 sepia and inky blue diazotype elements and four gelatin silver prints. It depicts four caryatids—female figures who form columns like those of the Erechtheion on the Athenian acropolis—holding up a temple facade.

The work is dark and disturbing, like much of Woodman’s oeuvre, and draws on an unexpected combination of influences: ancient Greek architecture, feminist strength and New York City bathrooms. Its composition suggests a blueprint, a plan for a quiet, sturdy, safe place supported by women.

Blueprint for a Temple II is part of a stunning solo exhibition that opened last week at Gagosian’s W. 24th Street space. It has not been seen since 1980 when it was included in a group show at the Alternative Museum in New York. The exhibition draws on material from across Woodman’s tragically short career, spanning the period from approximately 1975 through 1980.

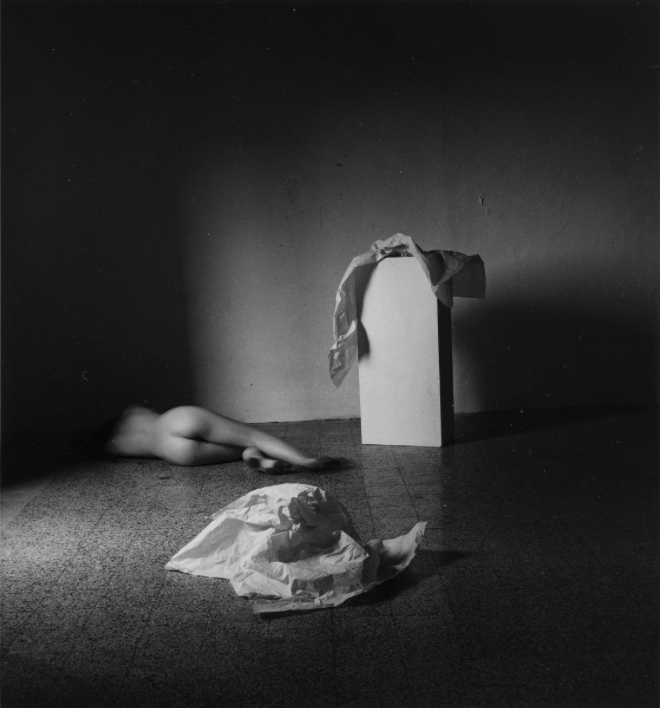

The 50 photographs that accompany the larger Temple piece and another monumental caryatid rendering are much smaller, many just a few inches square. They touch on the caliginous themes Woodman pursued while studying at the Rhode Island School of Design and while traveling in Italy. They are terrifying and sad portraits of decay and invisibility, of subjects obscured by their surroundings or fading into nothingness, of faceless figures surrendering to hopelessness and entropy.

Woodman, a tragic heroine of feminist art whose transformative work has inspired generations of women photographers, is one of photography’s most enigmatic figures. Her entire body of work consists of just 800 dark, introspective black-and-white prints made before she flung herself from a Lower East Side loft window in 1981 at the age of 22.

Francesca Woodman, Untitled, c. 1977–78, lifetime gelatin silver print,10 3/8 x 9 1/8 inches, © Woodman Family Foundation / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Copyright The Artist, courtesy Gagosian and The Woodman Family Foundation.

Blueprint for a Temple consists of photographs of Woodman’s friends and vintage interior design details projected onto architectural blueprint paper, according to her father, the artist George Woodman. It is now part of the permanent collection at the Met.

“The bathroom details were closely observed at friends’ apartments. The exalted caryatids were her friends posed in New York. But she had experienced at first hand the sublime caryatids of the Erectheum on the Acropolis in Athens when she was about 16 years old,” he wrote in 2012.

In an inscription on the piece, Woodman herself, explained her inspiration: “Bathrooms with classical inspiration are often found in the most squalid and chaotic parts of the city. They offer a note of calm and peacefulness like their temple counterparts offered to wayfarers in Ancient Greece.” she wrote. So in Woodman’s tormented world, it seems, a dilapidated loft in the Lower East Side and ancient Greek architecture are pretty much the same thing.

Corey Keller, who curated a 2011 retrospective of Woodman’s work at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art (SFMOMA), said that while the piece may appear at first to be well outside Woodman’s lane, it is actually a sort of culmination of her earlier work, coming as it did just a year before she died.

“They aren’t part of the Woodman mythology in the same way; it seems like a thing apart. And what the grouping in this show makes clear to me is that all her work was moving toward this, that the Temple was sort of a climax rather than an outlier,” Keller said in a recent conversation with Putri Tan, a director at Gagosian.

Keller went on to say that it is difficult to categorize Woodman as, say, a feminist photographer or a surrealist because her career was so short and she died so young. Though much of her work was created as a student, the exhibition at Gagosian demonstrates that it is hardly juvenilia.

“I think the reason we can’t quite pin her down is that she was still finding her way as an artist. She was an artist in formation, and artists in formation are exploring; they’re trying things out. So [in curating the SFMOMA show] I wanted to make room to appreciate that kind of youthful play, that self-exploration, which I felt hadn’t been admitted into the picture of Woodman yet,” Keller said.

That picture of the artist is drawn largely from the black-and-white prints and from her journals, including the collection Francesca Woodman: The Artist’s Books, published last year in association with the Woodman Family Foundation. The prints on display at Gagosian, some shown publicly for the first time, suggest an artist fascinated with the interplay between body, space, air and light.

Francesca Woodman, Untitled, c. 1977–78, lifetime gelatin silver print,111 3/4 x 9 3/8 inches, © Woodman Family Foundation / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Copyright The Artist, courtesy Gagosian and The Woodman Family Foundation.

“I’m interested in the way that people relate to space,” she said. “The best way to do this is to depict their interactions to the boundaries of these spaces. Started doing this with [ghost] pictures, people fading into a flat plane—ie becoming the wall under wallpaper or of an extension of the wall onto floor.”

At the same time, though, Woodman’s work suggests feminine struggles with fear, shame, pain, identity, sexuality and violence.

“Francesca’s work suggests violence and that there had been familiar aggression projected onto her work,” fashion and fine-art photographer Collier Schorr said during a panel discussion at Rizzoli Bookstore last summer.

“I look at the work and, yes, there’s shame, yes, there’s violence, but there’s also sexuality… We look at it and say that’s a really strong woman, but that’s a picture usually made by a male artist,” she said,

Photographer Moyra Davey added that Woodman’s photography was revolutionary in both subject and technique.

“Suddenly, there were these images that were just so extraordinary as was the way she was working…It was clear to me that she was a poet and someone who had a way with language and that she was just incredibly playful and agile with the way she used words with her photographs,” she said.

“She would take one or maybe two pictures and that was it. She wasn’t putting pressure on herself looking for the perfect image....It was unpredictable....She was using long exposures and timers and so she never knew exactly what she was getting; so every image would have been a surprise to her,” Davey added.

The Gagosian exhibition coincides with Francesca Woodman and Julia Margaret Cameron: Portraits to Dream In, a major survey at the National Portrait Gallery in London, on view from March 21 to June 16, before it travels to IVAM Institut Valencià d’Art Modern, Spain.

The New York show runs through April 27 at Gagosian, 555 West 24th St., Chelsea.

Originally published by Whitehot Magazine.