Daniel Root: Transcending Closing Time

Closing time, one last call for alcohol

So, finish your whiskey or beer

Closing time, you don’t have to go home

But you can’t stay here. – Semisonic

In their 1998 hit Closing Time, Semisonic summons the fleeting melancholy of a bar closing. Who doesn’t know that feeling, one minute you’re chatting away over a second PBR, next minute they’re putting the stools on the bar and the bartender’s giving you the gimlet eye?

While the song is a sad one, it ends on an optimistic note, a reminder that the melancholy that is attendant the closing of a bar is indeed a temporary state since within a few hours it will open again and the barroom life cycle will begin anew. “Every new beginning comes from some other beginning’s end,” they offer.

This duality between the mournful declaration of an end to a night’s revelry and the happy optimism of a springlike reopening is the theme of a new book from East Village photographer Daniel Root, New York Bars at Dawn, in which he captures watering holes in the Lower East Side and across New York City at their most revealing. His photographs are like a peak under the covers at a slice of the city in slumber, like watching a lover sleep.

Skulking the city before sunrise, Root photographed a diverse collection of more than 200 bars focusing on the kind of joints most people conjure when they think of downtown NYC.

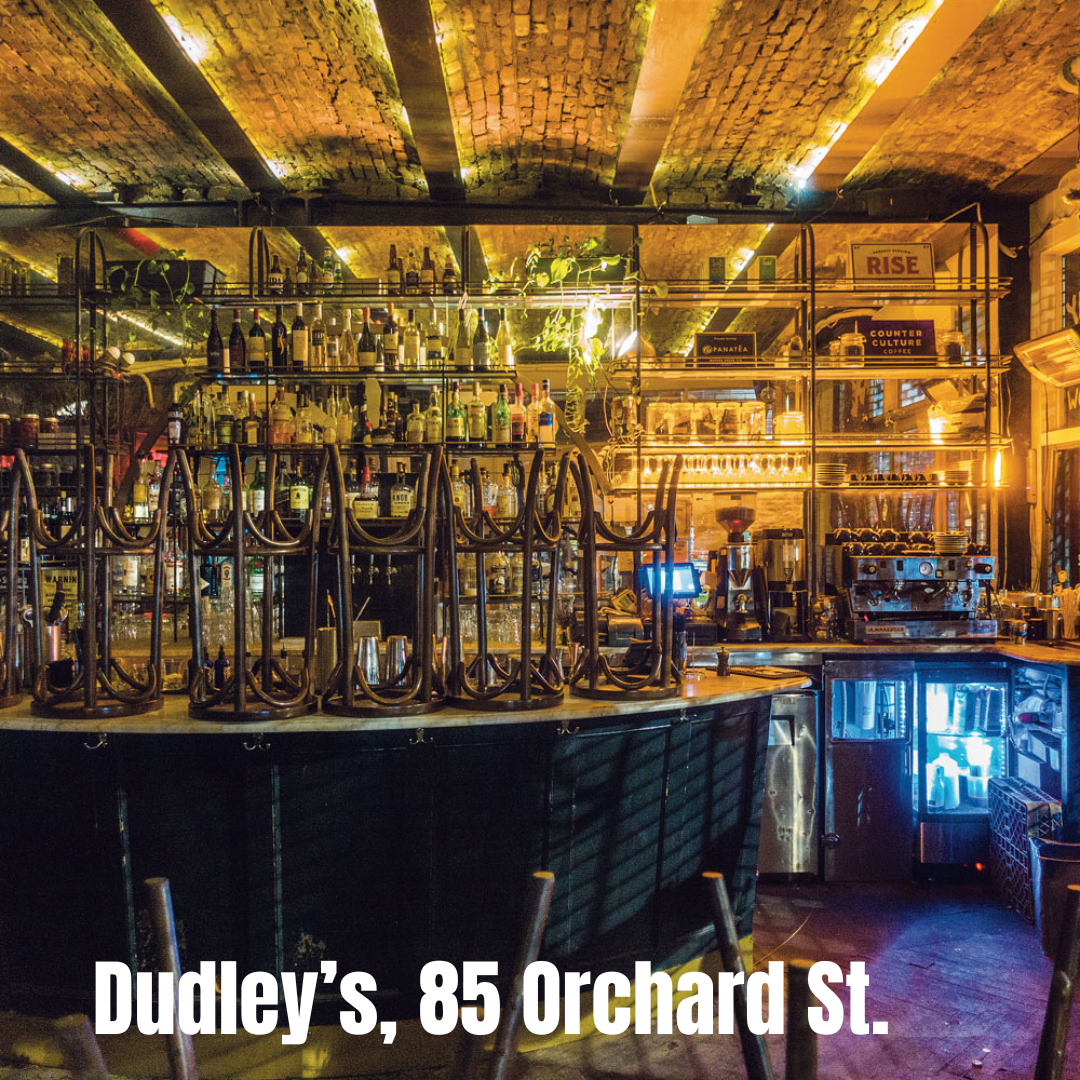

There are lots of tin ceilings, tiled floors, exposed brick, pool tables and, of course, the bars themselves and the backbars that hold the essential medicine on which auspicious nightlife depends. And while there are certainly differences between the bars Root has chosen as subjects, the photographs all reflect a certain New Yorkness, a hard-scrabble resilience and a sense of possibility and inevitability.

During a recent interview held at the very first bar that caught his photographer’s eye years ago, 7B, the East Village’s renowned “horseshoe bar” at the corner of 7th Street and Avenue B, Root explained how New York Bars at Dawn came to be.

“Walking in the morning just starts my day off better. And when you walk at 5 a.m. you notice things that you wouldn’t notice with people on the street….Take this place, the bathroom door may be left open, the party lights may be left on, the next time you walk by it may look completely different because a different bartender closed,” he said.

“I noticed the lighting in here, and then I noticed the lighting in Niagara (a block away at 7th and Avenue A)…and it just seemed like this whole world all of a sudden opened up just by one quick glance left as I walked by this place,” he added.

Over time, Root became particularly adept at taking advantage of the low light conditions he commonly found in closed bars before sun up. A flash would be unthinkable, not only because of the reflection it would cause, but because artificial light would rob the photographs of their essential shadowy essence. He discovered, though, that placing the camera’s lens directly against the window glass not only prevented reflection, it also steadied the camera to allow for much longer exposures, some as long as eight seconds.

Once perfected, Root’s technique allowed for the capture of images that he could not see with his naked eye. Tiny light sources bathe the spaces in a golden glow that is especially present as it reflects off the lines of bottles shelved on backbars. Light reflecting off floors and bar tops also gives the places a shimmering feel of cleanliness, which in many cases is unearned, and expectant wonder.

Take, for example, the shot of Avenue A’s Double Down, a joint that revels in its reputation as an unvarnished dive. The giant “You Puke You Clean” sign notwithstanding, the Double Down appears downright polished. Light, used effectively as Root does here, strips away the patina of spilled beer and vomit, to reveal the Double Down’s naked self.

Some shots, like that of the Mulberry Street Bar, signal a sense of permanence and history: cracks slithering across a tiled floor, an antique clock, an olden-days picture on the wall all give the photograph a feeling for the neighborhood’s sepia-toned past. Likewise Dudley’s on Orchard Street, Fanelli Cafe on Prince Street, Pete’s Tavern on 18th St. by Gramercy Park, and, of course, McSorely’s Old Ale House on E. 7th Street.

Then there are the oddball details, the bras hanging from the ceiling at Jeremy’s Ale House on Front Street, the photographs in the rafters at the Dead Rabbit on Water Street, the cacophonous graffiti on the walls at Clockwork on Essex Street, the used guitars on the wall in the faux pawn shop entryway to Beauty and Essex, also on Essex.

Perhaps what is most interesting about Root’s work is how it demonstrates that even without people, these spaces are possessed of personality and life. It’s quite easy to conjure from each shot an interpretive guess at what happened just hours earlier and what could happen hours hence. In this sense, New York Bars at Dawn captures the city asleep and conscious at the same time. The photographs present a New York that is waiting to happen. Another pregnant dawn. Some other beginning’s end.

Originally published by The Lo Down.